Note on the session by Poonam Muttreja at the Prof. Asha Bhende Memorial lecture, International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), January 2022

It is an honour and privilege for me to deliver this lecture in the memory of the Late Prof Asha Bhende and on a subject close to her heart: ‘Population’. She joined IIPS in 1963 as a Senior Health Educator and served the institute in various capacities. She retired from IIPS as the Professor and Head of the Department of Population Policies and Programmes in October 1988. Her book “Principles of Population Studies” (Co-authored with Prof. Tara Kanitkar) remains widely acclaimed among demographers, social scientists, and students.

Besides being an academician, Prof. Bhende was also a talented actor. However, her talent and passion for acting never came in the way of her academic prowess. I fondly remember her on this day.

I have chosen to talk on the Roadmap to Population Stabilisation for two reasons.

- With roughly 1.37 billion people, India is the second-most populous country in the world. According to the latest UN World Population Prospects report, by 2027, India is expected to take the top spot from China.

- PM Kulkarni in his recent paper on the demographic and Regional Decomposition of Prospective Population Growth for India between 2021 and 2101, estimates that India’s population size will peak at close to 1.66 billion around 2061 after which India’s population will begin to decline gradually

- A study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, Seattle, published in The Lancet, has predicted that India’s population may peak even earlier at 1.6 billion by 2048. This study also predicted a steep decline in the total fertility rate, which will drop to 1.3 along with the total population coming down to 1.1 billion by the year 2100.

Such projections about numbers should not be a cause for concern.

The population problem, I want to repeat problem, as many refer to it as, is not about numbers. It is about people. And even more importantly, it is about the agency, or lack of it, of Indian women.

In this Lecture, I want to argue that while there is much to celebrate on the numbers front, there is still a large unfinished agenda linked to population stabilization. And this has to do with addressing the reproductive rights of the unreached: specifically, those women who continue to have more children than they want to, and more broadly, a large majority of women – extending beyond the poor – who do not have the rights over their own bodies to be able to exercise control over marriage and fertility decisions.

Let me start with the good news on the numbers front. The recently released NFHS-5 data confirms – or should I say reconfirms once again – that India is well on the course towards population stabilization.

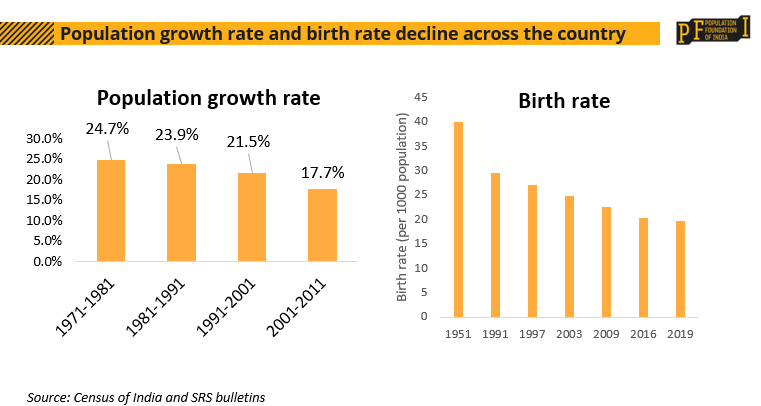

There has been a marked decline in India’s annual rate of population growth from 24.7% during 1971-81 to 21.5% in 1991-2001 and further to 17.7% in 2001-2011. India’s population growth rate is expected to decline to its lowest since the Independence in the 2011-2021 decade, with a decadal growth rate of 12.5%. And it is expected to decline further to 8.4% in the decade 2021-2031 decade.

India’s birth rate which was 40 per 1000 population in 1951 is down to less than 20.

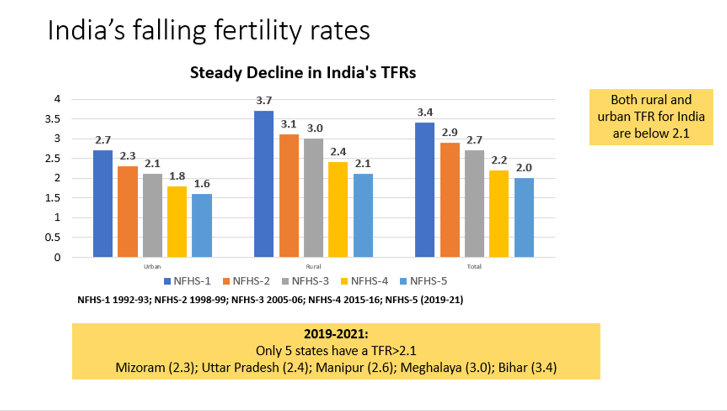

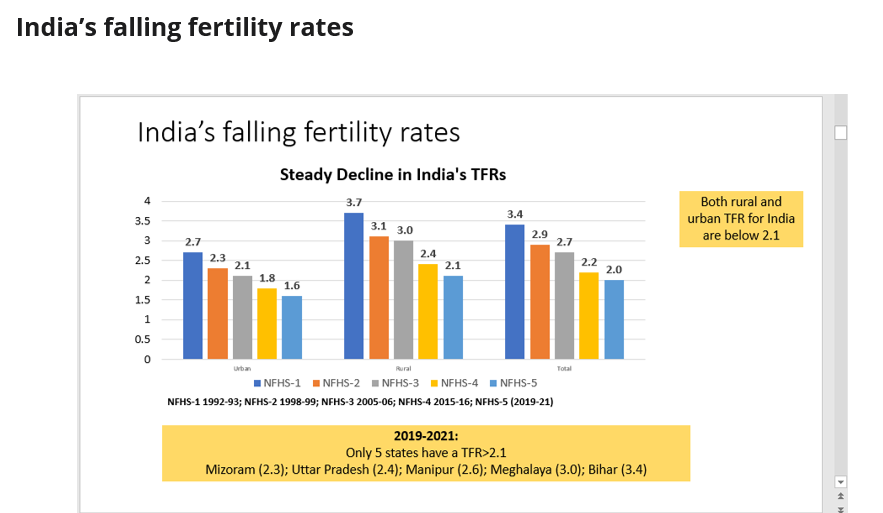

The NFHS surveys have also been debunking the myth of population explosion. NFHS-5 reaffirms what we always knew was bound to happen. India’s Total Fertility Rates have been steadily falling – across India, in rural areas and in urban areas. Five years ago, in 2015-16, even though the TFR had fallen to 2.2, very close to the replacement fertility rate and the urban TFR was down to 1.8 – below the replacement rate of 2.1, this was not the case with TFR in rural areas where it was at 2.4 – above the replacement rate of 2.1. Five years later, the situation is different today: India’s TFR is 2.1 or lower in both rural and urban areas.

Quite apart from India reaching the replacement level fertility of 2.1, it is quite an achievement that only 5 out of 28 states and 8 Union Territories have a TFR that exceeds the replacement level of 2.1: Bihar, Meghalaya, Manipur, Uttar Pradesh, and Mizoram.

In a lighter vein, I am glad that the term BIMARU state, coined by a renowned demographer, Ashish Bose, has dropped out of the population and development lexicon: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. I am sure if Prof Ashish Bose were alive today, he could not have resisted coining the more contemporary and appropriate acronym: BUMMM – Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, and Mizoram.

I mentioned earlier that population is not about numbers. It is about people. Population explosion is a myth, but I also want to debunk the myth about population growth and religions.

The declining trend in population growth and fertility is secular and can be seen among all religious groups. Let us not skirt the issue and look at the Hindu-Muslim question. Contrary to what could be a manipulated public opinion, it is not true that the Muslims have been growing faster than Hindus. The population growth rate for Muslims showed the highest decline of 4.7 percentage points between 2001 and 2011 as compared to the previous decade. The decline in Hindu population growth rate over the same period was 3.1 percentage points.

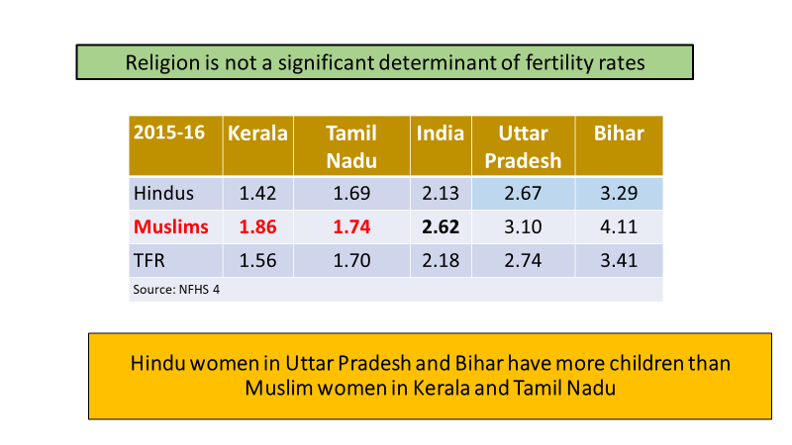

This Table shows the TFRs for two low fertility states, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and two high fertility states, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Two points are important to note. One, Muslim women in the southern states have lower fertility than Hindu women in the northern states. The TFR among Hindus of Uttar Pradesh (2.67) is higher than that of Hindus of Kerala (1.42); the fertility rate of Muslim in UP (3.10) is higher than the fertility rate of Muslims in Kerala (1.86). The fertility rate among Muslim women in Kerala (1.86) and Tamil Nadu (1.74) is lower than the fertility rate among Hindu women in Bihar (3.29) and Uttar Pradesh (2.67). What this establishes, however, is that there is no ‘Hindu fertility,’ ‘Muslim fertility’ or ‘Christian fertility’.

Two, across all states, the TFR among Muslim women is higher than among Hindu women – even in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. This is worrying, and I shall address this concern later

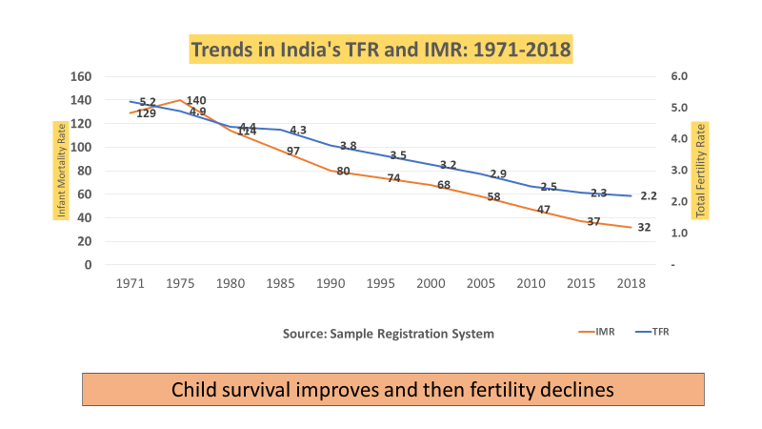

An important factor that has helped reduce fertility rates is child survival. Reduced child deaths are essential to lower fertility rates and population growth. Child survival improves and then after a generation or so, fertility rates decline. This is what you see in the graph: TFR and IMR declining in parallel but as one would expect, declines in TFR follow from declines in IMR.

Most significant in the decision-making by families is the replacement factor: the death of a child or the probability of a child dying would prompt many couples to ‘replace’ the loss by having many more children than they wanted. It will be difficult for us in this audience to recount even a single case of an infant death unless due to an extraordinary medical condition. Empirically, therefore, child survival improves and then after a generation or so, TFR declines. And that is what is displayed in the graph

Improvements in child survival gives confidence to young couples to decide the number of children they want to have. If a young couple today decides they want to have only one child, a majority of them can take such a decision with full confidence. The probability of that child dying is extremely low for most families and of surviving is extremely very high.

Let me move to the core of my lecture, that is, making a case for the unreached. The population battle has not been won as yet.

Averages hide huge disparities and inequalities. And that goes for the TFR as well. While there is reason to celebrate the fact that India’s TFR has come down to below the replacement levels, the disparities are worrying. Here again, we should not look at geographies but focus on people, women in particular.

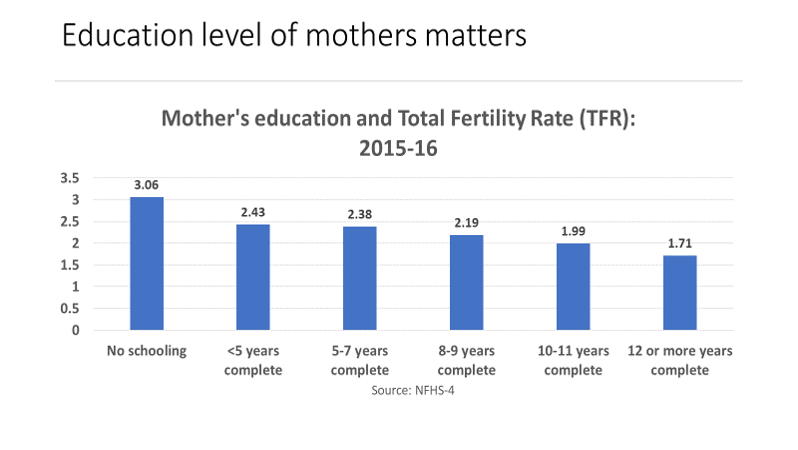

We know that fertility rates depend upon the level of the mother’s education.

In 2015-16, mothers with no schooling reported a TFR of over 3. On the other hand, mothers with 10 or more years of schooling reported a TFR of less than 2.

The real challenge lies in identifying a context where girls are not able to complete 10 or more years of schooling at do something about it. These are a major segment of the unreached populations whom we need to get to immediately.

NFHS-5 tells us that in 2019-21, only 41 per cent of women 15-49 years had completed 10 or more years of schooling. In rural India, it was just a little over one-third. In Kerala, more than three out of four women 15-49 years (77 per cent) had completed ten years or more of schooling – 75 percent in rural areas and 78 per cent in urban areas. Contrast this with the situation in Bihar where less than 30 per cent of women (28.8 per cent to be precise) had completed 10 or more years of schooling. Sadly, only 25 per cent of women 15-49 years in rural Bihar had completed 10 or more years of schooling in Bihar.

However, there is another matter of concern as well. If we noticed that the fertility rate among Muslim women is higher than among Hindu women across most states, there is a reason for this. According to the Sachar Committee report, Muslims have low-level access to educational opportunities and their educational attainment is as bad as or even worse than Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). A decade and a half later, the situation has not changed for Muslims. According to a recent NSSO report, the percentage of youth who are currently enrolled in educational institutions is the lowest among Muslims. Only 39% of Muslims in the age group of 15-24 are enrolled as against 44% for Scheduled Castes, 51% for Hindu OBCs and 59% for Hindu upper castes.

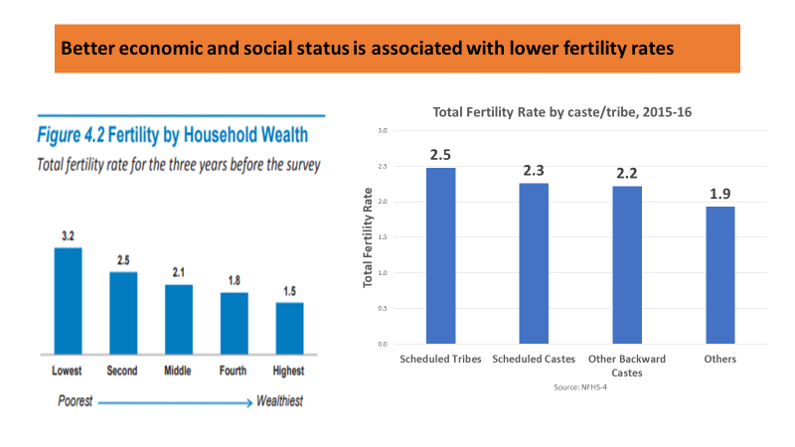

NFHS also reveals that the TFR among women in the lowest wealth quintile is above 3 whereas the TFR is lower than 2 in the higher wealth quintiles. Similarly, the TFR among Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Castes is above the replacement rate of 2.1.

This is where we have to understand the inter-sectionalities between caste, class and gender. Women who are least educated are likely to belong to the lowest wealth quintile and to socially backward communities. This is why I say that the population challenge still remains unsolved.

How do we lower the fertility rates among these categories of women?

Clearly, basic education plays an important role in reducing fertility. I am told that When the Chief Minister of Bihar, Nitish Kumar, was shown this graph, he immediately figured out what needs to be done to reduce the fertility rate in Bihar. His family planning program focused on giving a big push to girls’ education and ensuring that girls complete at least ten years of schooling. I am told this was the motivation behind giving bicycles to girls for them to attend school especially when it was not within walking distance.

It is equally important to ensure that the benefits of economic growth flow equitably to all sections of society.

The World Inequality Report 2022 brought out by the World Inequality Lab points out that India is among the most unequal countries in the world. The top 10% hold 57% of total national income and the bottom 50% merely 13% of total national income. According to the report, India stands out as a poor and very unequal country, with an affluent elite.

Clearly, India can be proud of its growth performance, but that is it. We need better policies to ensure equitable growth – to ensure that the benefits flow to a vast majority of people and not get concentrated in the hand of a few.

Let me move to the next segment of my lecture. I had mentioned in the beginning that in addition to reaching the unreached, it is important to reach out to a large majority of women – extending beyond the poor – who do not have the rights over their own bodies to be able to exercise control over marriage and fertility decisions.

We know that young girls have very little say over marriage decisions. The UDAYA survey on understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults conducted by Population Council points out that in 2015-16, in Bihar, 61% of married girls in the age group of 15-19 years had been excluded from exercising choice of husband and 77% of them were meeting their spouse for the first time on the wedding day.

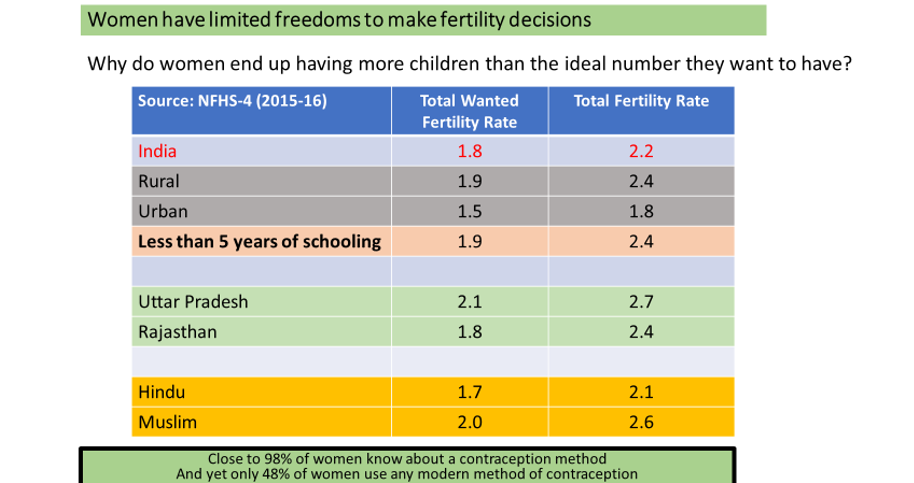

This lack of freedom spills over to fertility as well. In the ultimate analysis, the high fertility rate reflects the limited control women have over fertility decisions.

We know that women across India want to have two or fewer children.

The table shows the wanted fertility rate and the actual fertility rate. In 2015-16, women in both rural and urban India want to have fewer than two children but end up having more than two children.

Even women with less than five years of schooling want to have fewer than two children but end up having more than two children.

It is also important to note that Muslim women also want to have no more than two children – just like Hindu women.

Why is this so? It is because women do not have enough of a say over fertility decisions.

Unfortunately, even after noting that women are not able to even decide how many children they want to have, we find that the onus for family planning is entirely on women.

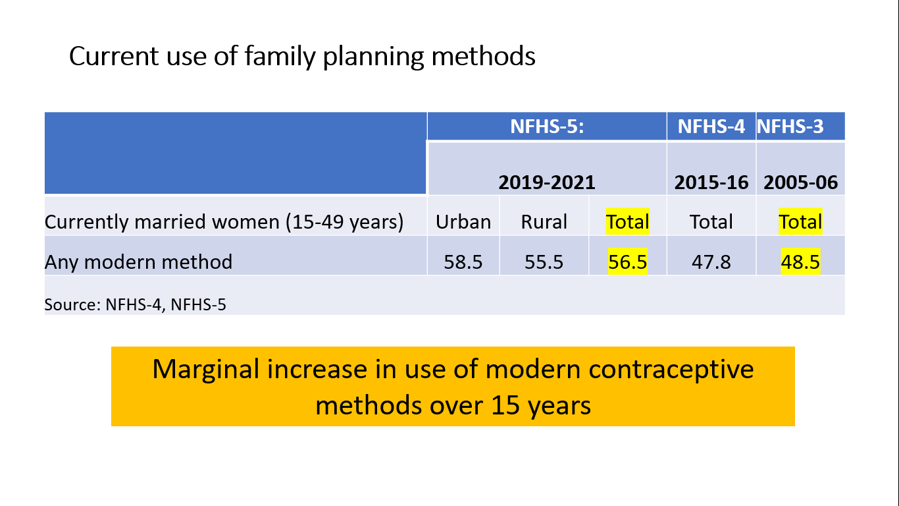

NFHS-4 informed us that close to 98 per cent of women know about a modern method of contraception. However, only 57 per cent of currently married women use a modern method of contraception. The increase over 15 years in the use of modern contraception methods has been marginal: from 49 per cent in 2005-06 to 57 per cent in 2019-21.

Why is this so? Once again, this only goes to show how little of a say Indian women have in family planning decisions.

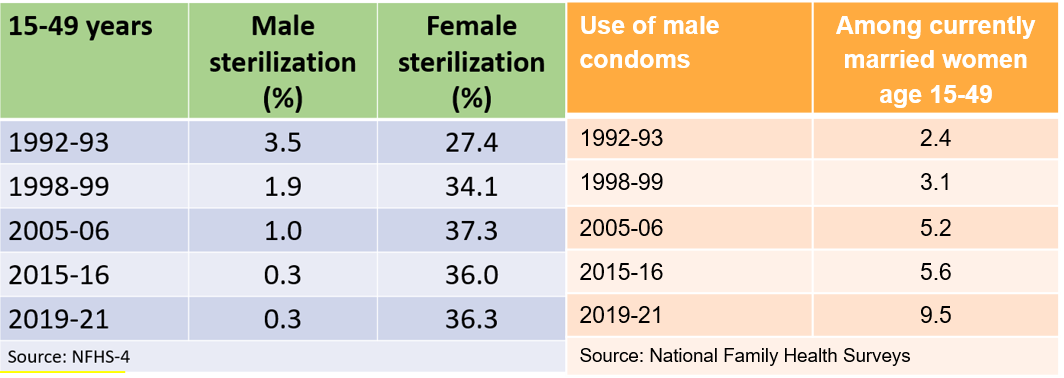

Sadly, female sterilization is the most commonly accessed modern method of family planning. This is in sharp contrast to male sterilization.

Even more revealing is the use of condoms by men.

We see that condom use is less than 10 per cent among currently married women. Once again, it reveals how difficult it is for women to convince men to take responsibility for family planning.

It is also important to note that there are close to 16 million abortions a year in India. Abortions have become yet another way of addressing the problem of unwanted babies – a sad option to adopting modern methods of contraception. The seriousness of the abortion issue stands out when the figure of 16 million abortions a year is juxtaposed against the 23-24 million babies who are born every year. This is truly a tragedy.

Behind the number of abortions, we often tend to forget the emotional trauma that women go through when they have to abort a foetus.

This is unfortunate given that India was among the first countries in the world to launch a national population policy in the 1950s. We also had a fairly successful family planning program – and many of you would remember the hum do-hamare do campaigns and the jingles that went with the social marketing campaign.

My favourtite is: Mia Bibi Tip Top; Do ke baad full stop!

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare continues to strengthen the family planning program and expand the basket of contraceptive choices in the public health system to meet people’s sexual and reproductive health needs.

In 2017, the Government of India introduced two new contraceptives, namely, an injectable contraceptive (Antara) and the centchroman pill (Chhaya) into the public health system.

The government also launched the Mission Parivar Vikas Programme (MPV) in 146 high focus districts of seven states with the highest total fertility rates in the country. The programme’s main objective is to increase access to quality family planning choices within a rights-based framework.

The Government’s efforts have yielded positive results. The total unmet need for family planning has declined from 12.9 percent in 2015-16 to 9.4 percent in 2019-21.

Quality of care in family planning has shown significant improvement: 62% of current users in 2019-21 reported having received information on side effects from service providers – up from 46 percent in 2015-16.

Despite the progress made by India on various health and fertility indicators, the discourse around the implementation of coercive population policies has been gaining momentum in recent times.

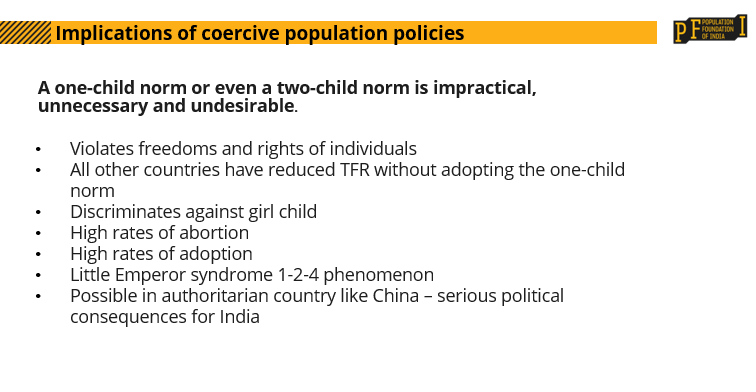

It is important to assert at this point that there is really no need to adopt China’s one-child policy or even enforce a two-child norm.

Stringent ‘population control’ measures (a term appropriate for referring to China’s measures) have created a population crisis for China. China introduced the one-child policy in the late 1970s in an attempt to boost economic progress by slowing down the rapid population growth, before reversing the decision in 2016 to allow families to have two children. In May 2021, the Chinese government further revised its policy and allowed couples to have up to three children – admitting that the consequences of such coercive measures were counterproductive. The strict birth limits have created a rapidly aging population and shrinking workforce that is straining the country’s economy. With this, one hopes that those who have been demanding that India emulate China in enforcing a one-child norm or a two-child limit will realize how misplaced their suggestion is.

Enforcing a one-child norm or even a two-child norm is impractical, unnecessary and undesirable. We should learn from China’s experience with the one-child policy which has had disastrous consequences.

To begin with, the number of children a couple wants to have should be a private decision. Any intervention by the state should be seen as a violation of fundamental rights.

In any case, no country in the world has adopted such a one-child policy to lower fertility rates. We can learn from within India itself – where Kerala, Tamil Nadu and other states have lowered fertility without enforcing any coercive measures.

China’s one-child policy has discriminated against the girl child. The skewed sex ratio at birth went on to reinforce son-preference and worsened the discrimination against the girl child. There were reports of high rates of abortion as well as the abandoning the girl child in adoption centres where they would often be treated very badly.

Sociologists have also pointed to the adverse effects of the Little Emperor syndrome that sets in when there is the only son in the family – pampered by the parents and grandparents. There are additional psycho-social problems that arise because of the 1-2-4 phenomenon – where the son may be required to bear the responsibility of supporting both of their parents and, sometimes, all four of their grandparents in their old age.

In any case, such measures could work in an authoritarian state like China but imposing them in India is likely to have serious political repercussions. The memories of forced sterilization are still vivid in people’s minds.

I am surprised the topic of a two-child norm is raked up quite frequently. Enforcing a two-child norm contradicts Government of India’s own position. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, in an affidavit filed in the Supreme court in December 2020 on a petition seeking implementation of a two-child norm, has clarified the government’s stand.

“International experience shows that any coercion to have a certain number of children is counter-productive and leads to demographic distortions. The Family Welfare Programme is voluntary in nature, which enables couples to decide the size of their family and adopt the family planning methods best suited to them, according to their choice, without any compulsion.”

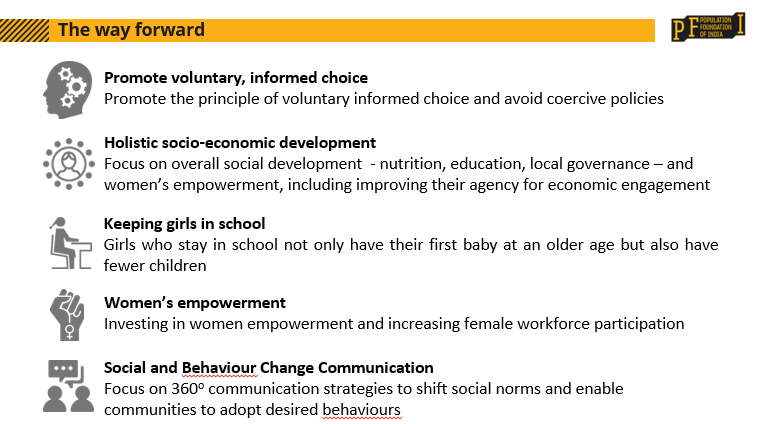

Therefore, instead of implementing coercive policies, we need to focus on addressing social determinants of health and changing social norms which deeply impact women’s health and fertility decisions and outcomes.

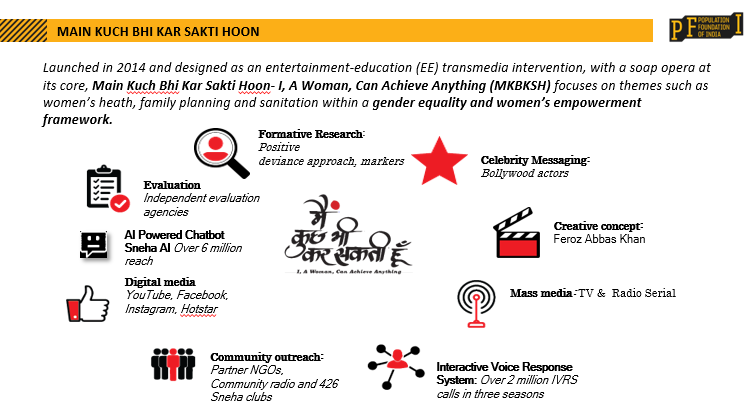

Experts on social and behaviour change communication have often made a case for entertainment education (edutainment) and transmedia storytelling as an effective way of influencing behaviour and social norms. Global evidence has demonstrated the efficacy of edutainment in changing mindsets which inspired Population Foundation of India’s (PFI) flagship edutainment initiative “Main kuch bhi kar sakti hoon- I, A Woman Can Achieve Anything” (MKBKSH). Directed by noted theatre and film director Feroz Abbas Khan– the vision behind MKBKSH was to create a “new normal” in a society where women have equal rights, equal access, equal agency as men.

- Launched in 2014, the core of the initiative was a radio and television drama series, whose messages were reiterated using a transmedia approach.

- A total of 183 episodes over three seasons of MKBKSH have been broadcast till date over Doordarshan (DD) and All India Radio (AIR).

- The serial has been aired in 12 languages across 50 countries, on DD national, DD regional Kendras, DD India and 216 radio stations.

- Millions have viewed the series and it received more than 2 million calls from viewers on its IVRS from 400,000 unique numbers across 29 states.

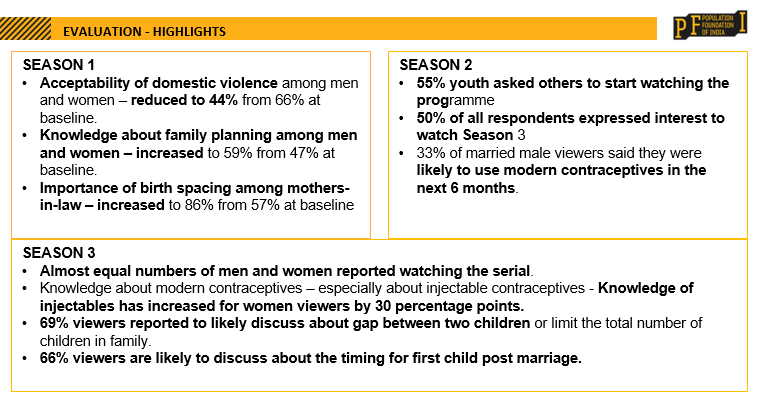

Let me highlight some of the results of third-party independent evaluations conducted after each season. We observed a positive shift in knowledge, attitudes and perception among viewers.

In Season 1, for instance, acceptability of domestic violence fell from 66% in the baseline survey to 44% in the endline study

At the end of Season 2, 33% of married male viewers said they were likely to use modern contraceptives in the next 6 months.

In Season 3:

- almost equal numbers of men and women reported watching the serial.

- Knowledge of injectables increased for women viewers by 30 percentage points.

Many more such initiatives are needed to bring about changes in mindsets.

Targeted social and behaviour change communication strategies are needed to address social norms that constrain women’s agency and reproductive autonomy.

We must empower our women to decide if, when and how many children they should have.

There is an unfinished agenda for the government to reach the last mile—the most marginalized, the poor and the young population, especially adolescents in order to address their unmet need for reproductive and family planning services.

Finally, the differential impact of the COVID-19 has affected women and girls across all spheres, including education, health, nutrition, safety, economic security and access to technology, threatening to reverse decades of progress made towards achieving gender equality. Gender must be central to COVID-19 recovery measures as well as future pandemic preparedness.

This is where we need new partnerships between the government, private sector experts, researchers, sociologists and other professionals, community-based organizations and frontline workers, NGOs and others.

Before I conclude, I want to point out that it is extremely important to be aware of the politics of language in this space. It is unfortunate to hear media anchors and others using the term population control. This term population control treats women as objects whose fertility can be controlled by policy actions. It brings back memories of the Emergency when State power was used against helpless citizens to forcibly sterilize women and men.

To end then, even though the news on the numbers front is encouraging, there is much that needs to be done to address the reproductive rights of the unreached. This calls for investing in expanding the freedoms for girls and women. More specifically, it requires increased investments:

- in women’s education

- in women’s health – adolescent and reproductive health

- in creating job opportunities for women; and

- in SBCC to change social norms, treat women with respect and dignity, and increase the participation of men in planning families

As we all know, human development is defined as an enhancement of capabilities, an expansion of freedoms, a widening of choices, and an assurance of human rights. In this sense, human development is the best contraceptive. If we take care of people, the population will take care of itself

I would like to end my lecture with a quote from Mr JRD Tara, eminent industrialist and founder of Population Foundation of India:

“I have always believed that no real social change can occur in any society unless women are educated, self-reliant and respected. Woman is the critical fulcrum of family and community prosperity”

Thank you once again for this opportunity to share my thoughts with you.