Mothers with almost no haemoglobin, two-years-olds weighing 7 kilos, alcoholism, low incomes and falling access to the forest are spurring acute malnutrition amongst Adivasi women in Gudalur, Tamil Nadu

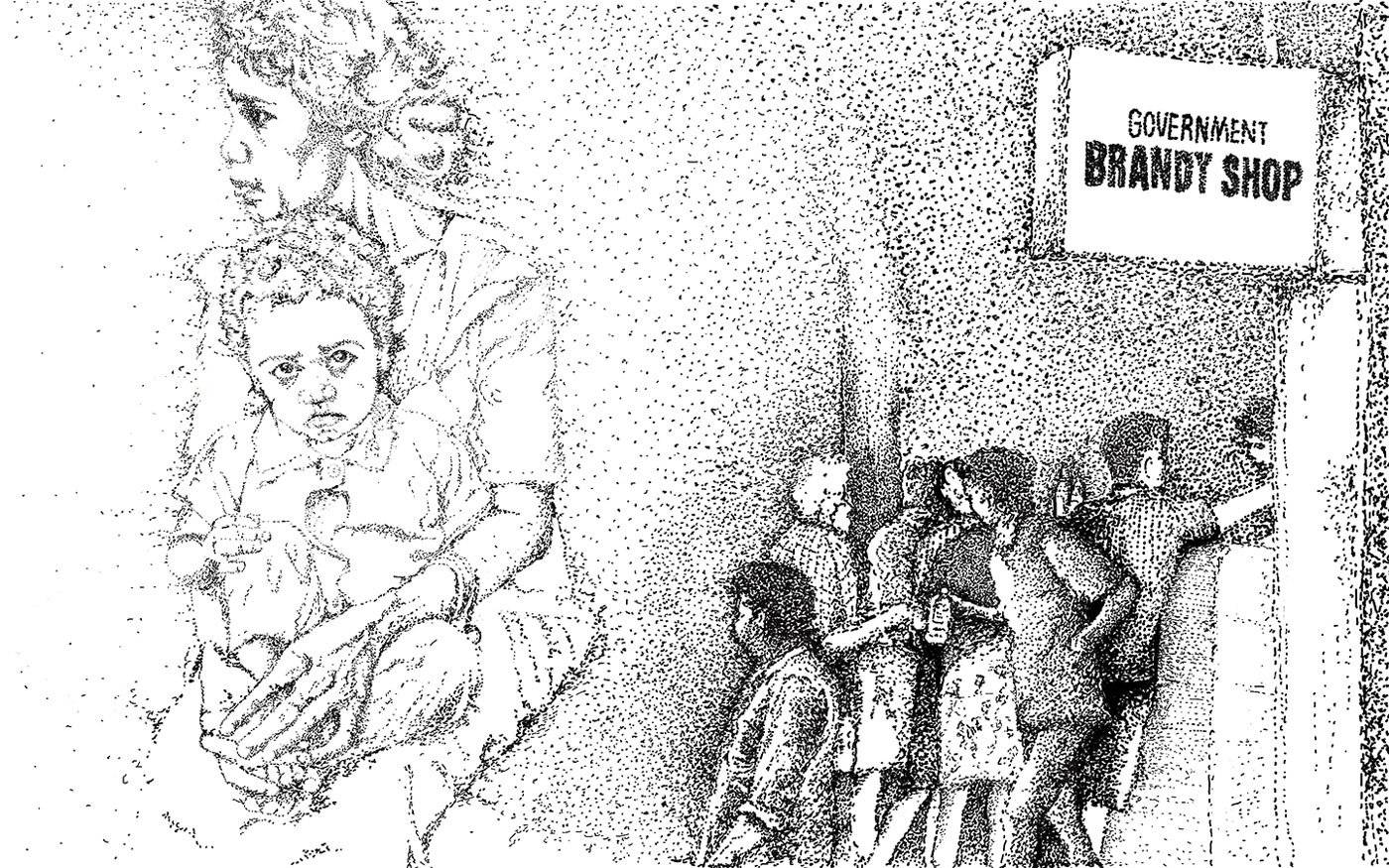

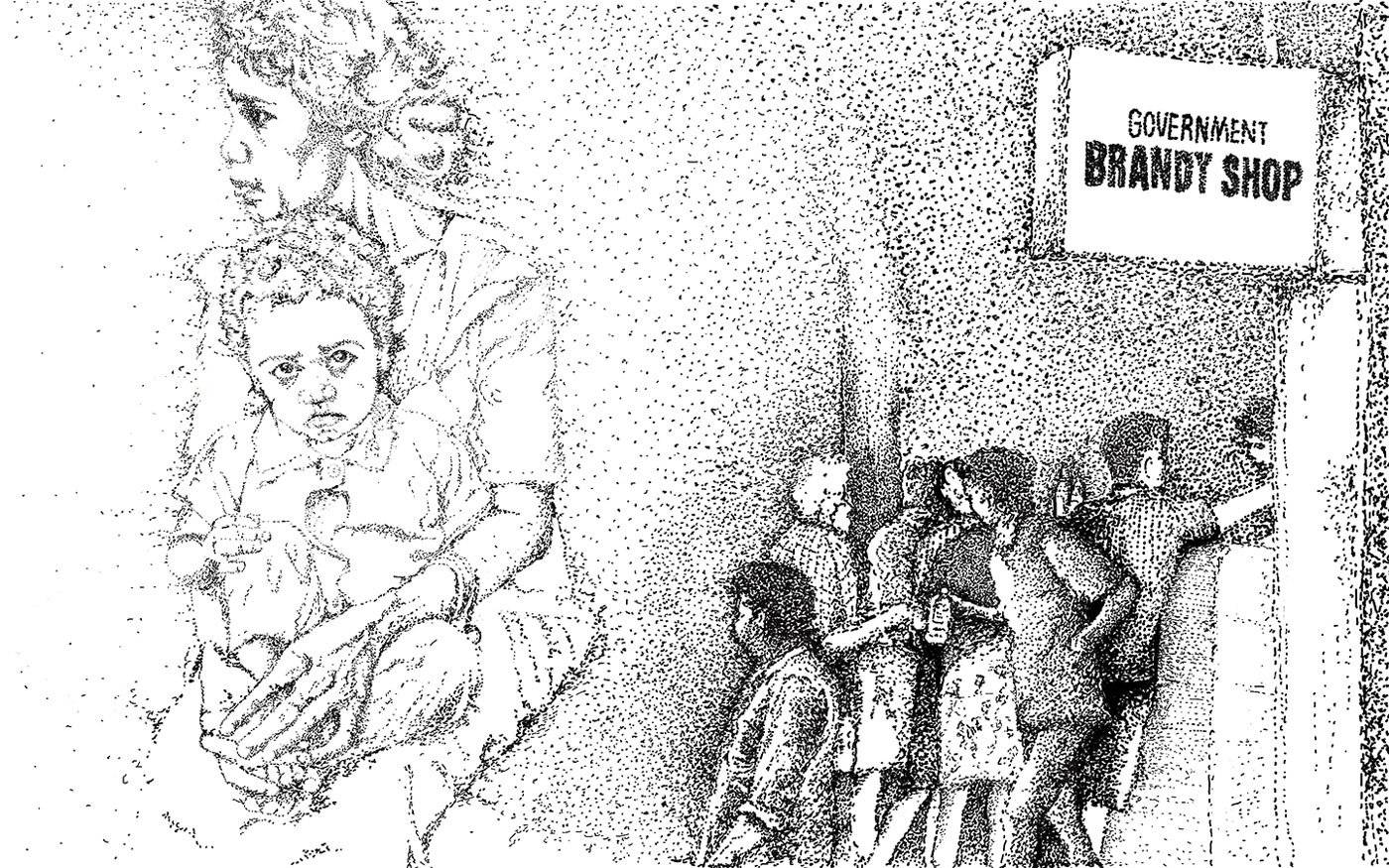

“My husband buys three bottles of alcohol on Saturday this size,” says Kanaka, holding up her fully-extended hand. “He drinks them over the next two or three days and goes back to work when the bottles are empty. There is never enough money for food. I can barely feed myself and my child, and my husband wants another child. I don’t want this life!” she adds, despairingly.

Kanaka (name changed) is a 24-year-old Betta Kurumba Adivasi mother waiting to see the doctor at the Gudalur Adivasi Hospital. The 50-bed hospital in Gudalur town, 50 kilometres from Udhagamandalam (Ooty), provides services to the 12,000-plus Adivasi population of Gudalur and Panthalur talukas in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu.

Slightly built and dressed in a faded synthetic saree, Kanaka is here for her only child, a daughter. At a regular check-up the previous month in her hamlet, 13 kilometres from the hospital, a health worker from the Association for Health Welfare in the Nilgiris (Ashwini), allied to the hospital, was alarmed to find Kanaka’s two-year-old weighing just 7.2 kilograms (the ideal is 10-12 kilos by age two). That weight placed her in the severely malnourished range. The health worker had urged Kanaka and her daughter to visit the hospital immediately.

The child’s malnutrition is not surprising, given the extent to which Kanaka must stretch the family income. Her husband, also in his 20s, works only a few days a week as a daily wage labourer in the nearby tea, coffee, banana and pepper estates, earning about Rs. 300 a day. “He gives me only 500 rupees a month for food,” Kanaka says. “With that I have to cook for the whole family.”

Kanaka and her husband live with his aunt and uncle, both daily wage labourers in their 50s. Together, the family has two ration cards, which entitles them, every month, to 70 kilograms of free rice, two kilos of dal, two kilos of sugar and two litres of oil at subsidised rates. “Sometimes my husband even sells our ration rice to buy alcohol,” Kanaka says. “On some days there is nothing to eat.”

The Gudalur Adivasi Hospital in the Nilgiris district –this is where young women like Kanaka and Suma come seeking reproductive healthcare, sometimes when it’s too late

The state’s nutritional programmes do not appear to be sufficient to supplement Kanaka and her child’s meagre diet either. At the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) balwadi near her hamlet in Gudalur, Kanaka and other pregnant and lactating mothers get one egg a week and a two-kilo packet of dry sathumaavu (a porridge of wheat, green gram, groundnuts, gram and soya) every month. Children under the age of three also get a monthly packet of the same sathumaavu. After age three, children are expected to go to the ICDS centre for breakfast, lunch, and an evening snack of a handful of peanuts and jaggery. Extra peanuts and jaggery are handed out to severely malnourished children every day.

Since July 2019, the government has also begun issuing the Amma Uttachathu Pettagam nutrition kit to new mothers, containing ayurvedic supplements, 250 grams of ghee, and 200 grams of protein powder. But Jiji Elamana, 32, the community health programme coordinator at Ashwini, says, “The packet just lies on the shelf in their house. The reality is that tribal people don’t use milk and ghee in their diet, so they don’t touch the ghee. And they don’t know how to use the protein powder and the green ayurvedic powder, so they put it aside.”

There was a time when Adivasi communities in the Nilgiris had easy access to food from the forests. “Adivasis are extremely knowledgeable about the tubers, berries, leafy greens and mushrooms which they collect,” says Mari Marcel Thekaekara, who has been working with Gudalur’s tribal communties for four decades. “They would also fish and hunt small animals for food throughout the year. Most homes would have some meat drying above the cooking fires for a rainy day. But then the forest department began limiting their entry into the forests and finally stopped it completely.”

Despite the restitution of community rights over common property resources under the Forest Rights Act of 2006, the Adivasis are not able to supplement their diet with resources gathered from the forest as they did before.

The falling incomes in village here are also contributing to the growing malnutrition. K.T. Subramanian, secretary of the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam, says that over the last 15 years, wage labour options for Adivasis have steadily reduced as the forests here became the protected Mudumalai wildlife sanctuary. The small plantations and estates within the sanctuary – where most of the Adivasis found work – were sold off or relocated, forcing them to seek intermittent work in the bigger tea estates or farms.

Adivasi women peeling areca nuts – the uncertainty of wage labour on the farms and estates here means uncertain family incomes and rations

In the same Gudalur Adivasi Hospital where Kanka is waiting, 26-year-old Suma (name changed) is resting in a ward. She is a Paniyan Adivasi from neighbouring Panthalur taluka, and has recently given birth to her third child, a girl like the others, aged two and 11 years. Suma didn’t give birth at this hospital, but has come for post-delivery care and a tubal ligation procedure.

“I was a few days overdue, but we did not have the money to come here for the delivery,” she says, referring to the cost of travelling from her hamlet, an hour away by jeep. “Geetha chechi [the health worker at Ashwini] gave us 500 rupees for the travel and food, but my husband spent it on alcohol. So I remained at home. Three days later, my pains intensified and we had to leave, but it was too late to get to the hospital so I delivered at the PHC close to my house.” The next day, the nurse at the primary health centre called 108 (the ambulance service) and Suma and family were finally on their way to the GAH.

Four years ago, Suma had a miscarriage in the seventh month due to intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), a condition in which the foetus is smaller or less developed than its gestational age. The condition is often the result of the mother’s poor nutritional status, anaemia and folate deficiency. Suma’s next pregnancy was also impacted by IUGR, and her second child, a daughter, was born severely underweight (1.3 kilograms against an ideal birth weight of over 2 kilos). The child’s age to weight graph is well below the lowest percentile line, marked in the chart as ‘severely malnourished’.

“If the mother is malnourished, the child is going to be malnourished,” points out Dr. Mridula Rao, 43, family medicine specialist at GAH. “Suma’s baby is likely to bear the impact of her mother’s poor diet; her physical, intellectual and neurological growth will be slower than that of other children her age.”

Suma’s own patient record shows that she gained only five kilograms during her third pregnancy. This is less than half the stipulated gain for pregnant women of normal weight, and much less than half for underweight women like Suma – at nine months she tipped the scales at a mere 38 kilos.

Despite the restitution of community rights under the Forest Rights Act of 2006, the Adivasis are not able to supplement their diet with resources gathered from the forest as they did before

Though many families in Gudalur have similar stoies to tell, steady gains seem to have been made in the health indicators in this block. Hospital records show that the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 10.7 (per 100,000 live births) in 1999 had dropped to 3.2 by 2018-19, and the infant mortality rate (IMR) had declined from 48 (per 1,000 live births) to 20 during the same period. In fact, the State Planning Commission’s District Human Development Report 2017 (DHDR 2017) records Nilgiri district’s IMR at 10.7, lower than the state average of 21, with Gudalur taluka recording an even lower 4.0.

Such indicators though don’t tell the whole story, explains Dr. P. Shylaja Devi, who has worked with Adivasi women in Gudalur for the last 30 years. “Mortality indicators such as MMR and IMR have definitely improved, but morbidity has increased,” she says. “We need to distinguish between mortality and morbidity. A malnourished mother will produce a malnourished child who will be susceptible to illnesses. Such a three-year-old can quickly die of something like diarrhoea, and her intellectual growth is slow. This will be the next generation of Adivasis.”

Besides, the gains in routine mortality indicators are being undermined by increasing alcoholism amongst the tribal communities in the region, and may mask high levels of malnutrition amongst Adivasi populations. (The GAH is in the process of putting together a paper on the correlation between alcoholism and malnutrition; it’s not yet publicly available.) As the DHDR 2017 report points out, “even when mortality is controlled, the nutritional status may not improve.

“While we were controlling other causes of death such as diarrhoea and dysentery, and making all deliveries institutional, alcoholism in the community was rendering it all to waste. We are seeing sub-Saharan levels of malnutrition and compromised nutritional status among young mothers and their children,” says Dr. Shylaja, 60, a obstetrics and gynaecology specialist who officially retired from GAH in January 2020, but still spends every morning at the hospital, meeting patients and discussing cases with her colleagues. “And 50 per cent of children are now moderately or severely malnourished,” she observes. “Ten years ago [2011-12], moderate malnutrition was 29 per cent and severe malnutrition was 6 per cent. So this is a very, very disturbing trend.”

Left: Family medicine specialist Dr. Mridula Rao and Ashwini programme coordinator Jiji Elamana outside the Gudalur hospital. Right: Dr. Shylaja Devi with a patient. ‘Mortality indicators have definitely improved, but morbidity has increased’, she says

Describing the evident effects of malnutrition, Dr. Rao adds, “Earlier, when mothers came to the outpatient department for check-ups, they would be playing with their children. Now they sit around with apathetic expressions, and the children also look very dull. This apathy translates into lack of care for their children and their own nutritional health.”

“We still have Adivasi women who come with practically no blood – 2 grams per decilitre of haemoglobin! When you are checking for anaemia you put the hydrochloric acid and pour the blood, so the minimum it can read is 2 grams per decilitre. It could be lower, but we can’t measure that,” says Dr. Shylaja.

There is a close link between anaemia and maternal deaths. “Anaemia can result in obstetric haemorrhage, cardiac failure and death,” points out Dr. Namrita Mary George, 31, the gynaecology and obstetrics specialist at GAH. “It also causes intrauterine growth restrictions in the baby, and neonatal deaths due to low birth weight. The baby fails to thrive and chronic malnutrition sets in.”

Early marriage and early pregnancies further endanger the health of the child. NFHS-4 states that only 21 per cent of girls in rural parts of the Nilgiris are married before the age of 18 years, but health workers here argue that most Adivasi girls they work with are married by the age of 15 or soon after their first menstrual period. “We need to do more with regard to both delaying marriage and delaying the first child,” admits Dr. Shylaja. “When girls get pregnant at the age of 15 or 16, before they have had a chance to grow into full adults, their poor nutritional status will adversely impact the health of the newborn.”

An Alcoholics Anonymous poster outside the hospital (left). Increasing alcoholism among the tribal communities has contributed to malnutrition

Shyla chechi (‘big sister’), as she is referred to by both patients and colleagues, has an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of tribal women’s issues. “Family health is tied to nutrition, and pregnant and lactating women are doubly at risk from a lack of nutritious food. Wages have gone up, but the money is not reaching the family,” she points out. “We know of cases where men collect their 35 kilograms of ration rice and sell it in the next shop to buy alcohol. How can malnutrition in their children not increase?”

“Any meeting we have with the community, on any topic, will eventually end with this problem: rising alcoholism in families,” says Veena Sunil, 53, mental health counsellor at Ashwini.

The Adivasi communities in this area are mostly Kattunayakan and Paniyan, ranked as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups. Over 90 per cent of them work as agricultural wage labour on farms and estates, notes a study done by the Tribal Research Centre, Udhagamandalam. The other communties here are mainly the Irular, Betta Kurumba and Mullu Kurumba, listed as Scheduled Tribes.

“When we first came here in the 1980s, despite the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act of 1976, Paniyas continued to work as bonded labour on paddy, millet, plantain, pepper and tapioca plantations,” says Mari Thekaekara. “They were in small plantations deep inside the forest, unaware that they had land titles to the very land they worked on.”

Mari, along with her husband Stan Thekaekara, founded ACCORD (Action for Community Organisation, Rehabilitation and Development) in 1985 to address the issues faced by Adivasis. Over time, the donations-run NGO has formed a network of organisations – sangams (councils) were set up and brought under the umbrella Adivasi Munnetra Sangam, run and controlled by Adivasis. The Sangam has managed to reclaim tribal land, establish a tea plantation and set up a school for Adivasi children. ACCORD also started the Association for Health Welfare in the Nilgiris (Ashwini), and in 1998 the Gudalur Adivasi Hospital was established. It now has six doctors, a laboratory, X-ray room, pharmacy and blood bank.

Left: Veena Sunil, a mental health counsellor of Ashwini (left) with Janaki, a health animator. Right: Jiji Elamana and T. R. Jaanu (in foreground) at the Ayyankoli area centre, ‘Girls in the villages approach us for reproductive health advice,’ says Jaanu

“In the ’80s, Adivasis were treated like second-class citizens in the government hospital here and they would run away. The health situation was dire: women were dying regularly during pregnancy, and there was diarrhoea and death in children,” recalls Dr. Roopa Devadasan. She and her husband Dr. N. Devadasan were pioneering Ashwini doctors who went from house to house in tribal areas. “We would not even be allowed into the home of a sick or pregnant patient. It took a lot of talking and reassuring before the communities began to trust us.”

Community medicine is at the heart of Ashwini, which has 17 health animators (health workers) and 312 health volunteers – all Adivasis themselves – who travel extensively across Gudalur and Panthalur talukas, visiting homes and giving advice on health and nutrition.

T. R. Jaanu, now in her 50s, who is from the Mullu Kurumba community, was one of the first health animators trained at Ashwini. She has an office in Ayyankoli hamlet of Cherangode panchayatin Panthalur taluka, and does regular checks among Adivasi families for diabetes, hypertension and tuberculosis, and dispenses first aid as well as advice on general health and nutrition. She also keeps track of pregnant and lactating mothers. “Girls in the villages approach us for reproductive health advice several months into their pregnancy. Folate deficiency tablets must be given in the first three months to prevent intrauterine growth restriction or it won’t work,” she points out.

For young women like Suma though, IUGR could not be prevented. At the hospital a few days after we meet, her tubal ligation has been completed, and she and her family are packing to go home. They have been counselled on nutrition by the nurses and doctors. She has also been handed money for her travel home and to buy food for the next week. “This time, we hope, the money will be used as directed,” says Jiji Elamana, as they leave.

Cover illustration: Priyanka Borar is a new media artist experimenting with technology to discover new forms of meaning and expression. She designs experiences for learning and play, juggles with interactive media, and also feels at home with traditional pen and paper.

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org