In Bihar’s villages, during the lockdown last year, teenage girls were married off to young male migrant workers who returned home. Many are now pregnant and anxious about what comes next.

Both are 17, both are pregnant. Both of them collapse easily into giggles, sometimes forgetting parental instructions to keep their gaze down. And both are terrified of what comes next.

Salima Parveen and Asma Khatun ( names changed ) were both in Class 7 last year, though the government-run village school was closed right through the academic year of 2020. As the lockdown wore on, the men in their families who had been away working in Patna, Delhi and Mumbai came home to Bangali Tola, a hamlet in Bihar’s Araria district. A small flurry of matrimonial alliances followed.

“Corona mein hui shaadi,” says Asma, the more talkative of the two. “I got married during corona.”

Salima’s nikaah (wedding ceremony) had been solemnised two years earlier, and she was to begin to cohabit with her husband when she was closer to 18. Then the lockdown hit, and her 20-year-old husband, who works as a tailor, and his family – they live in the same hamlet – insisted that she move in. That was around July 2020. He was without work and at home all day, the other men were at home too – and an extra hand would be useful.

Asma had even less time to steel herself. Her 23-year-old sister died of cancer in 2019 and in June last year her sister’s husband, a plumber, insisted on marrying Asma during the lockdown. The ceremony took place in June 2020.

Neither girl knows how babies are born. “These things are not explained by the mother,” says Rukhsana, Asma’s mother, as the girls giggle some more. “ Laaj ki baat hai [It is an embarrassing matter].” Everybody agrees that the bride’s bhabhi , her brother’s wife, is the correct source of this and other information, but Salima and Asma are sisters-in-law and neither is in any position to offer child-bearing advice.

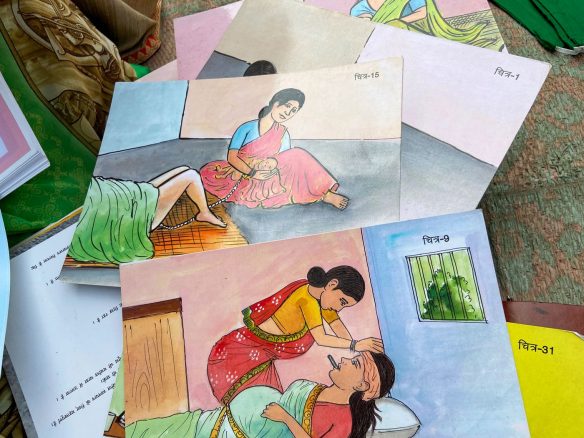

Health workers with display cards at a meeting of young mothers in a village in Purnia. Mostly though everyone agrees that the bride’s bhabhi is the correct source of information on such matters

Asma’s aunt, who is the ASHA worker (accredited social health activist) of Bangali Tola – the hamlet in Belwa panchayat of Raniganj block has around 40 families – promises to explain everything to the girls “soon.”

Or the girls could ask Zakiya Parveen, just two years their senior and new mother to 25-day-old Nizam (names changed), who has an unblinking kohl-lined stare and a black smudge from the kohl placed on a cheek to ward off the ‘evil eye’. Zakiya is now 19, she says, though she looks much younger, the billowing folds of her cotton saree making her look even more frail and pallid. She never went to school, and was wedded to her cousin when she was about 16.

Health workers and researchers too observe that many of Bihar’s ‘Covid child brides’ are now pregnant, fighting low levels of nutrition and information. However, adolescent pregnancies even before the lockdown were common across Bihar’s villages. “This is not uncommon here, young girls get pregnant right after the wedding and have a baby in the first year,” says Block Health Manager Prerna Verma.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019-20) notes that 11 per cent of all girls in the 15-19 age bracket were already mothers or were pregnant at the time of the survey. Bihar accounts for 11 per cent of all of India’s early marriages among girls (before the age of 18), and 8 per cent of early marriages among boys (before age 21).

Another 2016 survey in Bihar shows this too. Done by the Population Council, a non-profit that works on health and development issues, it notes that among girls aged 15-19 years, 7 per cent were married before the age 15. In rural areas, as many as 44 percent of girls who were 18-19 were married before they turned 18.

Meanwhile, many of Bihar’s young brides, married during last year’s lockdown, have been living in unfamiliar surroundings without a spouse, after their husbands returned to the cities for work.

Early marriage and pregnancies combine with poor nutrition and facilities in Bihar’s villages, where many of the houses (left), don’t have toilets or cooking gas. Nutrition training has become a key part of state policy on women’s health – an anganwadi worker in Jalalgarh block (right) displays a balanced meal’s components

Zakiya’s husband, who works in a zari embroidery unit in Mumbai, left days after Nizam arrived this January. She is not consuming any post-partum nutritional supplements, and the state-mandated calcium and iron for the months after childbirth are yet to be supplied, though she did receive the ante-natal supplements correctly from the anganwadi .

“Aloo ka tarkari aur chawal [cooked potatoes and rice],” she says, listing her daily food intake. No lentils, no fruits. Worried that her baby could suffer from jaundice, Zakiya’s family has prohibited her from eating non-vegetarian food or eggs for the immediate future. The family has a milch cow tethered at their doorstep, but Zakiya will not be given milk for a couple of months. All these food items are believed to be a source of jaundice.

The family is particularly protective of Nizam, conceived nearly two years after Zakiya was married at the age of 16. “We had to take her to a baba in Kesarara village. We have relatives there. He gave us a jadi [herb] for her to eat, and she conceived soon after that. It is a junglee dawa [wild medicinal plant],” says Zakiya’s mother, a homemaker (her father is a labourer). Will they take her back to Kesarara, about 50 kilometres away, if she does not conceive a second child in time? “No, the second child will come when Allah gives us a child.”

Zakiya has three younger sisters, the youngest still to turn five, and an elder brother, around 20 years old, who too works as a labourer. The sister all attend school and a madarsa. Zakiya was not enrolled due to the family’s limited finances.

Did she require stitches for a perineal tear post-childbirth? Zakiya nods. Does it hurt? The girl’s eyes fill with tears, but she doesn’t speak, instead returning her gaze to little Nizam.

A test for under-nourished mothers – the norm is that the centre of the upper arm must measure at least 21 cms. However, in Zakiya’s family, worried that her baby could get jaundice, she is prohibited from consuming non-vegetarian food, eggs and milk

The two other pregnant girls ask if she cried during childbirth, and the women gathered around laugh. “Bahut royi [a lot],” Zakiya says clearly, the loudest she has spoken until now. We are all sitting in the semi-constructed home of a somewhat better-off neighbour, on borrowed plastic chairs placed on loose cement lying in heaps on the floor.

The World Health Organisation notes (in its Global Health Estimates 2016: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2016) that globally, adolescent mothers in the 10 to 19 age group face greater risk of eclampsia (seizures and high blood pressure before or during or after childbirth), puerperal (six-week period after childbirth) endometriosis and infections than women aged 20-24 years. There are risks for newborns too, from low weight at birth to more serious neonatal conditions.

Araria’s Block Health Manager Prerna Verma has one more concern for Zakiya. “Don’t go to your husband,” she advises the teenage mother – repeat pregnancies for very young mothers are a reality that health workers in Bihar’s villages are familiar with.

Meanwhile, Salima, who is one month pregnant (in February, when I visited), is still to be registered for ante-natal care at the local anganwadi . Asma is six months pregnant, her belly still only a small bump. She’s begun receiving ‘taakati ka dawa’ (medicines for strength), calcium and iron supplements that the state provides for all pregnant women for 180 days.

But NFHS-5 notes that only 9.3 per cent of mothers in Bihar consumed iron folic acid for 180 days or more during their pregnancy. Only 25.2 per cent of mothers had at least four ante-natal care visits to a health facility.

Asma smiles nervously as her mother explains why the prospective groom would not wait a year to marry her. “The boy’s family felt some other boy in the village would elope with her. She was going to school, after all, and these things do happen in our village,” Rukhsana says.

The National Family Health Survey (2019-20) notes that 11 per cent of all girls in the 15-19 age bracket were already mothers or were pregnant at the time of the survey.

*****

The 2016 Population Council survey (titled Udaya – Understanding Adolescents and Young Adults) also dwelt upon emotional, physical and sexual violence against girls by their husbands: 27 per cent of married girls aged 15 to 19 had been slapped at least once, and 37.4 per cent had been forced to engage in sex at least once. Also, 24.7 per cent of married girls in this age group felt pressured by family members to bear a child immediately after marriage, and 24.3 per cent felt fear of being labelled ‘barren’ if she did not bear a child soon after marriage.

Anamika Priyadarshini, who is based in Patna and leads research at ‘Sakshamaa: Initiative for What Works, Bihar’, says it was clear that the lockdown exacerbated the challenge of tackling child marriage in the state. “On the Bandhan Tod app launched by the UNFPA-state government in 2016-17, there were several reports or complaints of child marriages,” she says. The app offers information about issues such as dowry and sexual crimes, and has an SOS button that lets a user contact the nearest police station.

In January 2021, Sakshamaa, which is planning a detailed survey of child marriages, prepared a report assessing exiting schemes, titled ‘Early Marriage in India with Special Reference to Bihar’. Anamika says that schemes to defer girl children’s marriage through improving their education, various other state interventions, conditional cash transfers, and other measures have had mixed results. “Some of these programmes certainly have a positive impact. For example, a cash award to keep girls in school, or the bicycle scheme for girls in Bihar raised their enrolment in secondary schooling and also gave them more mobility. Even if the beneficiaries of these programmes tend to marry upon reaching 18 years of age, it is still welcome,” she says.

On why the Prevention of Child Marriage Act, 2006, is not properly enforced, the report says, “There are no publicly available studies regarding the effectiveness of legal enforcement of child marriage laws in Bihar. However, studies conducted in other states like Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, West Bengal, and Rajasthan have found that law enforcement agencies struggle to implement PCMA because of political patronage, and influence of organised vested interest groups and networks.”

In other words, with its wide social acceptance, including among the politically connected or privileged, child marriage is not easy to prevent. Also, the practice is linked closely with cultural and religious beliefs, making state intervention a delicate matter.

Many young women who are pregnant learn about childbirth from display cards such as these. But 19-year-old Manisha Kumari of Agatola village says she doesn’t have much information about contraception, and is relying mostly on fate to defer another pregnancy

About 50 kilometres east of Araria, in Purnia district’s Purnia East block, Manisha Kumari of Agatola village is nursing her one-year-old son in the soothing shade of her mother’s verandah. She says she is 19. She doesn’t have much information about contraception, and is relying mostly on fate to defer another pregnancy. Her younger sister Manika, 17, is beginning to wilt under the family’s pressure to marry. Their mother is a homemaker, and father works as a farm labourer.

“My sir has said the minimum age for marriage is 18 years,” says Manika. She is referring to a teacher at the Purnia city residential school she was studying in Class 10, until the lockdown imposed in March 2020 brought her home. The family is unsure of sending her back – many more things are unaffordable this year. With her homecoming, Manika faces the prospect of her marriage being finalised. “Everyone is saying get married,” she says.

In neighbouring Ramghat, a hamlet of around 20-25 families, Bibi Tanzila is a grandmother to an eight-year-old boy and a two year old girl at the age of 38 or 39 years. “If a girl is unmarried at 19, she is considered a budhiya [old woman], nobody will marry her,” says Tanzila. “We are Shershahbadi Muslims, we follow our religious texts very strictly,” she adds, explaining that contraception is prohibited, and girls are married off a few years after attaining puberty. She was a bride at the age of about 14 and, a year later, a mother. After the fourth child, she developed complications and underwent a sterilisation procedure. “In our sect, nobody gets an operation done out of choice,” she says about hysterectomies and tubal ligation, which is Bihar’s most popular method (NFHS-5) of birth control. “Nobody says we have 4-5 kids and cannot look after any more.”

The Shershahbadi Muslims of Ramghat own no farmland, the men depend on daily wages as labourers in nearby Purnia city while some migrate farther to Patna or Delhi, and some work as carpenters or plumbers. Their name, they say, comes from the town of Shershahbad in Malda, West Bengal, named after Sher Shah Suri. They speak Bengali among themselves, and live in tightly knit community clusters, often derisively referred to as Bangladeshi.

Women of the Shershahbadi community in Ramghat village of Purnia

The village’s ASHA facilitator, Sunita Devi, says government intervention in family planning and birth control has had only marginal results in hamlets like Ramghat, where education levels are low, child marriage is common and contraception expressly prohibited. She introduces the very young 19-year-old Sadiya (name changed) , a mother of two, who delivered her second boy in May 2020, during the lockdown. Her two children were born about 13 months apart. Sadiya’s husband’s sister has begun to take an injectable contraceptive, with her husband’s permission – he is the local barber – persuaded more by their own financial distress than the ASHA’s remonstrations.

Tanzila says times have begun to change slowly. “Of course childbirth was painful, but not as much in those days as it appears to be today. Maybe it is just poor nutrition levels in the food we eat nowadays,” she says. She knows some women in Ramghat have begun to use contraceptive pills, or injections, or even an intra-uterine device. “Stopping conception is wrong, but nowadays people don’t have a choice, it seems.”

Back in Araria’s Bangali Tola, some 55 kilometres away, Asma declares that she hasn’t quit school. School was closed due to the lockdown when she got married and went away to Kishanganj block, 75 km away. Back in February 2021 to live with her mother after a health scare, she says she will be able to walk to her school, the Kanya Madhya Vidyalaya, after she delivers the baby. Her husband will not mind, she says.

Probed about the health event, it is Rukhsana who answers: “I got a call one evening from her parents-in-law, she had experienced some bleeding. I took a bus and rushed to Kishanganj, we were all scared and crying. She had gone out to use the toilet, and there must have been something in the wind, a chudail .” A baba was summoned for a ritual to protect the mother-to-be. Back home, Asma told the family she felt she should see a doctor. The next day, they took Asma to a private clinic in Kishanganj town where an ultrasound confirmed that the foetus was unharmed.

Asma smiles at the memory of her own agency, however faint. “I wanted to make sure the baby and I are in good health,” she says. She doesn’t know about contraception, but the conversation has piqued her curiosity. She wants to find out more.

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org