Child and adolescent brides in Bihar’s Patna district have no choice but to keep producing babies until they deliver a boy. For them, social custom and prejudice override laws and legal pronouncements.

Rani Mahto is torn between happiness over the safe delivery of her now two-day-old baby – and apprehension over going home and telling her husband that it’s a girl. Again.

“He was expecting a son this time,” she says nervously. “I worry about how he will react when I return home and tell him our second child is also a girl,” says the 20-year-old as she breastfeeds the infant in her bed at the Danapur Sub-Divisional Hospital in Bihar’s Patna district.

Rani had her first daughter soon after getting married at the age of 16 in 2017. Her husband Prakash Kumar Mahto was 20 at the time. She lives with Prakash and her mother-in-law in a village she prefers not to name – in Phulwari block of the same district. The Mahtos belong to a conservative OBC community.

“In our village, most of the girls get married by the age of 16,” says Rani who is not ignorant of the problems arising from marriage while still an adolescent. “I have a younger sister, too, so my parents were keen to get me married off at the earliest,” she says, as her mother-in-law, Ganga Mahto joins her and sits on the bed waiting for the chutti wale paper (discharge certificate).

Rani and her sister are by no means exceptions. Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Maharashtra and Rajasthan account for 55 per cent of all child and adolescent marriages in the country, says the NGO Child Rights & You (CRY) in an analysis of Census, National Family Health Surveys and other official data.

“Once we get the chutti wale paper,” Rani explains to me, “we will hire an autorickshaw to our village.” She has already spent two days longer than normally necessary in the hospital. Because she has other medical problems demanding attention. “I have khoon ki kami (anaemia),” says Rani.

Rani is worried about her husband’s reaction to their second child also being a girl

Anaemia is a severe public health problem especially among women, adolescent girls and young children in India. Research studies, both official and independent, show that girls who marry early have a higher likelihood of suffering from food insecurity, malnutrition and anaemia. And that child marriage is closely tied to low levels of income and education. Poor families with high food insecurity often see early marriages as a way of reducing the financial burden on their households.

Girls who marry early often have very little say in decisions concerning their own health and nutrition. The entire process sparks off a cycle of ill-health, poor nutrition, anaemia and low birth weight in children. Child marriage, one driver of this process, also becomes one of its outcomes. And then, there’s a further problem that complicates any policymaking on this: who is a child in India?

The 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child – India is a signatory since 1992 – defines as a child any individual who is not yet 18. In India, the laws on child labour, marriage, trafficking and juvenile justice have varying definitions of minimum age. In our law on child labour, that age is 14. The law relating to marriage states that a female attains majority only at 18. In India, different laws also make distinctions between ‘child’ and ‘minor.’ Consequently, youngsters in the age group 15-18 often slip through the cracks of administrative action.

In Rani Mahto’s life, in any case, the rigid realities of social custom and gender prejudice were and are always more powerful than any laws or legal pronouncements.

“When Rakhi [her elder daughter] was born, my husband didn’t talk to me for weeks. He would stay over at his friends’ twice or thrice a week and come home drunk.” Prakash Mahto is a labourer but works barely half of each month. “My son doesn’t try getting work,” says his mother Ganga sadly. “He might work 15 days in a month – but then spends all he earns entirely on himself in the next 15. Alcohol is ruining his life, and ours too.”

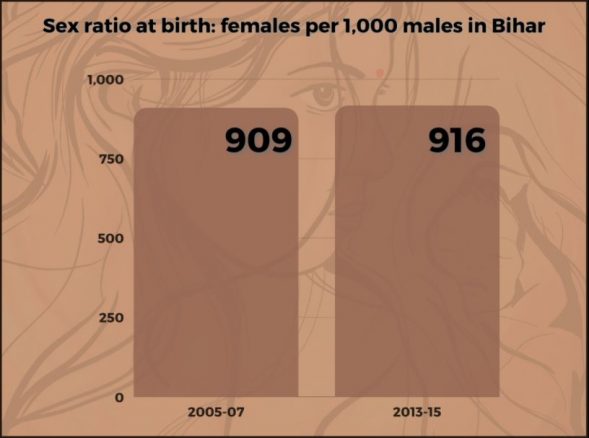

Left: The hospital where Rani gave birth to her second child. Right: The sex ratio at birth in Bihar has improved a little since 2005

The ASHA worker in Rani’s village suggested she undergo tubal ligation after her second delivery. But her husband would not agree. “ASHA didi suggested that I not have more than two children. She said that because of anaemia my body is too weak to bear a third child. So, when I was four months pregnant, I tried talking to Prakash about having that operation, post-delivery. But that turned into a nightmare for me. He told me if I wanted to live in his house, I needed to give him a boy, no matter how many pregnancies it takes. He refuses to use any kind of precautions and if I insist, I get slapped. My mother-in-law also agrees with him on the idea of not getting operated and trying for a son.”

That she is able to speak openly in front of her mother-in-law suggests the bond between the two women is not a negative one. Just that Ganga, otherwise sympathetic to Rani, cannot break free of the patriarchal mindset ruling her society.

The National Family Health Survey-4 suggests that only 34.9 percent of people in Patna (Rural) use any kind of family planning methods at all. Among the listed methods, male sterilisation in the rural part of the district actually logs zero percent. NFHS-4 also indicates that 58 per cent of pregnant women in Bihar, in the age group 15-49, are anaemic.

“With a second delivery at the age of 20, I have decided on one thing,” says Rani. “And that is: there is no way I would get my girls married before they turn 20, at least. In my case, I will have to keep producing babies till I give birth to a son.”

She sighs but says calmly: “Women like us have no option but to do as our aadmi (man) says. You see, the lady on the third bed from mine? She is Nagma. It was her fourth delivery yesterday. In her home too, they dismissed any idea of getting her bachchedani (uterus) removed. But now that she is here with her parents and not in-laws, she’ll get it done after two days. She is very daring. She says she knows how to deal with her husband,” Rani smiles, wistfully.

A UNICEF report notes that, like Rani, most child brides give birth during their adolescence. Also, their families are found to be bigger in size than those of the women who marry later. And the pandemic has made things worse.

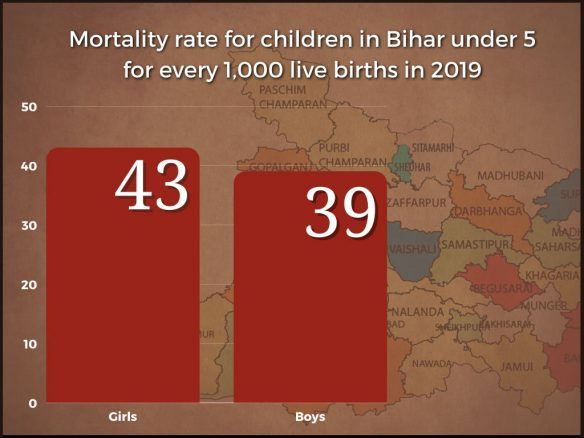

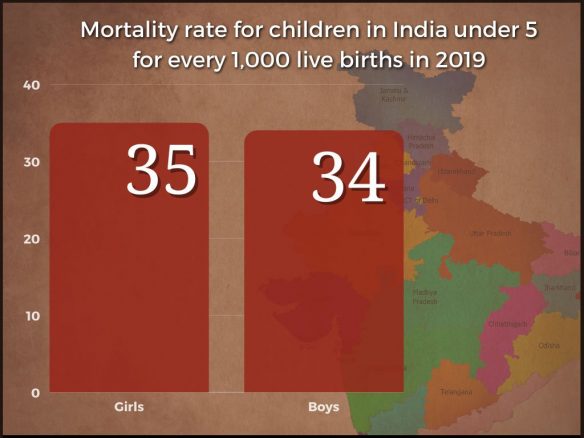

Bihar’s sex ratio widens after birth as more girls than boys die before the age of five. The under-5 mortality rate in Bihar is higher than the national rate

“The goal of ending child marriage by 2030 already seemed like a challenge,” says Kanika Saraff. “You only had to look at the situation in the rural areas of any state in the country to recognise that.” Kanika Saraff is the head of child safety systems in Aangan Trust, Bihar, which is strongly focused on child protection. “But the pandemic,” she says, “has added more layers to the problem. We were able to stop 200 child marriages in Patna alone in this period. So you can imagine the conditions in other districts and their villages.”

The sex ratio at birth in the state of Bihar, according to the Niti Aayog, was 916 females to every 1,000 males in 2013-15. This was seen as an improvement over 2005-07 when it was 909. Hardly reassuring though, as the sex ratio deteriorates further as more girls than boys die before the age of five. That is, the under-5 mortality rate (the probability of deaths by age five for every 1,000 live births) is 43 girls to 39 boys in the state. The All-India figure was 35 females to 34 males in 2019, according to estimates by UN agencies.

Ganga believes that a grandson would bring happy days to the family – something she acknowledges her own son could not. “Prakash is of no use. He never went to school after class five. That is why I wish to have a grandson. He would take care of the family and his mother. Rani could not get the kind of nutritious food a pregnant woman needs. She could not even speak for the past two days because of weakness. That’s why I stayed in the hospital with her and asked my son to leave.

“When he comes home drunk, and my daughter-in-law questions it, he hits her and smashes various household items.” But isn’t this a dry state? Even after being declared as such, nearly 29 percent of men in Bihar consume alcohol, says NFHS-4. Among rural males that’s almost 30 percent.

During Rani’s pregnancy, Ganga tried looking for work as a maid outside her village, but without success. “Looking at my condition, and seeing me fall sick,” says Rani, “my mother-in-law finally borrowed some five thousand rupees from a relative to bring me fruits and milk occasionally.”

“I am not sure what will happen to me in coming days if they keep me producing babies,” says Rani reflecting ruefully on her complete lack of control over her body and life. “But if I stay alive, I will try to get my girls educated as much as they want.”

“I don’t want my daughters to end up like me.”

The names of some people and locations have been changed in this story to protect their identities.

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalized groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org

Jigyasa Mishra reports on public health and civil liberties through an independent journalism grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this reportage.