In Adivasi hamlets in a reservoir area of Odisha’s Malkangiri, amid thick forests, high hills, and the state-militant conflict, erratic boat services, and broken roads are the only ways to reach sparse health facilities

The nearest hope of medical help was a two-hour ride by a boat that runs on the reservoir of a dam. The alternative was traversing a high hill across a partially constructed road.

And Praba Golori was nine months pregnant and very close to childbirth.

When I reached Kotaguda hamlet around 2 in the afternoon, Praba’s neighbours had gathered around her hut expecting the baby would not make it.

Praba, 35, had lost her first child when he was three months, her daughter is now about six years old. She had delivered them both at home, with the help of local dais, traditional birth attendants, and without much trouble. But this time the dais were hesitant, they had assessed it was going to be difficult childbirth.

I was in a nearby village that afternoon covering a story when the phone rang. Taking a friend’s motorbike (my usual Scooty cannot manage these hilly roads), I rushed to Kotaguda, a hamlet of barely 60 people in Odisha’s Malkangiri district.

Other than its inaccessibility, the hamlet in Chitrakonda block, like other parts of the Adivasi belt of Central India, has witnessed recurring conflicts between Naxalite militants and the state’s security forces. Roads and other infrastructure in many places there remain poor and sparse.

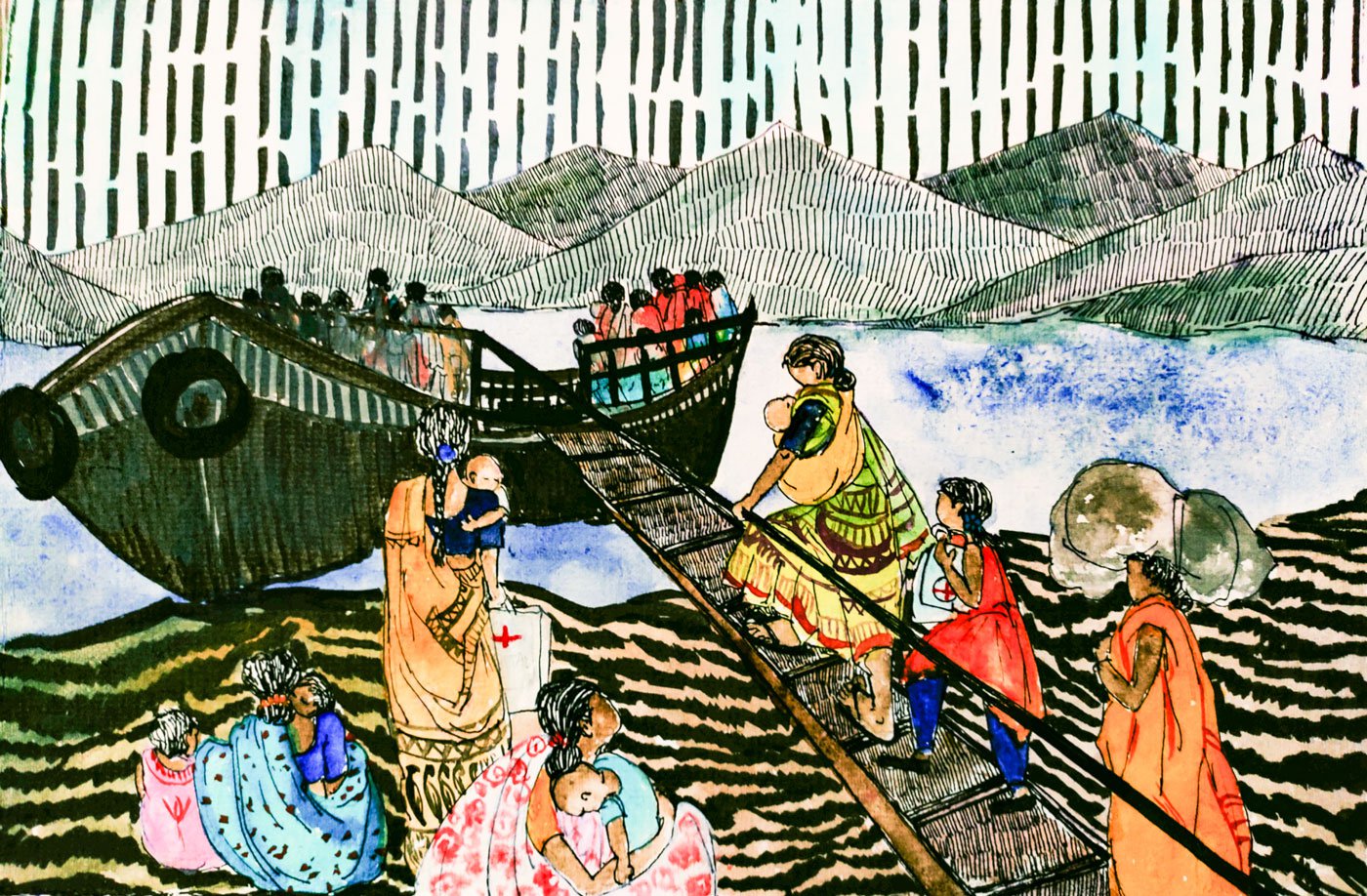

To help Praba Golori (left) with a very difficult childbirth, the nearest viable option was the sub-divisional hospital 40 kilometres away in Chitrakonda – but boats across the reservoir stop plying after dusk

The few families who live in Kotaguda, all from the Paroja tribe, mainly grow turmeric, ginger, pulses and some paddy for their own meals, as well as a few other crops to sell to buyers who come visiting.

At the nearest primary health centre five kilometres away in Jodambo panchayat, visits by doctors are irregular. And with the lockdown, the PHC was closed when Praba’s baby was due in August 2020. The community health centre in Kudumuluguma village is about 100 kilometres away. And this time, Praba would require a surgery, which the CHC cannot handle.

So the nearest viable option was the sub-divisional hospital 40 kilometres away in Chitrakonda – but boats across the Chitrakonda/Balimela reservoir stop plying after dusk. The route across the high hills would require a motorbike or an arduous walk – options entirely unsuitable for nine-month pregnant Praba.

I tried to get help through people I know at Malkangiri district headquarters, but they said that sending an ambulance across the bad roads was difficult. The district hospital has a water ambulance service, but that too could not make the journey due to the lockdown.

Then I managed to convince a local ASHA (accredited social health activist) to come with a private pick-up van. That cost around Rs. 1,200. She could only come the next morning.

The state’s motor launch service is infrequent, with the unscheduled suspension of services. A privately-run boat too stops plying by evening. So in an emergency, transportation remains a huge problem

We started out. The van soon broke down on the uphill under-construction track across which we were taking Praba. We then spotted a tractor of the Border Security Force looking for firewood and requested them to help. They took us to the top of the hill where a BSF camp is located. The personnel at that camp in Hantalguda arranged for Praba’s transportation to the sub-divisional hospital in Chitrakonda.

At the hospital, the staff said she would have to be taken to Malkangiri district headquarters, 60 kilometres away. They helped to arrange the onward vehicle.

We reached the district hospital late in the afternoon, a day after I had first rushed to Kotaguda.

There, Praba bore three days of agony when the doctors and medical staff tried to induce labour with no success. Finally, we were told that she would have to undergo a caesarean operation.

It was August 15, and Praba’s baby boy was born that afternoon – he weighed a fairly healthy three kilos. But the doctors said his condition was serious. The baby did not have an opening to pass faecal waste and an immediate surgery was necessary. The hospital at the Malkangiri district headquarters, however, was not equipped to conduct this procedure.

The baby would have to be admitted to a newer and bigger facility at Saheed Laxman Nayak Medical College and Hospital in Koraput, around 150 kilometres away.

Kusama Naria (left), nearly nine months pregnant, walks the plank to the boat (right, in red saree) for Chitrakonda to get corrections made in her Aadhaar card

The baby’s father, Podu Golori, was in utter despair by now and the mother was still unconscious. So the ASHA worker (who had first come with a van to Kotaguda hamlet) and I took the baby to Koraput. It was around 6 in the evening on August 15.

The hospital ambulance we were travelling in broke down after just three kilometres. The second one we managed to call broke down after another 30 kilometres. We waited in the thick jungle with pelting rain for yet another ambulance to arrive. We finally reached Koraput, then under lockdown, after midnight.

There, the doctors kept the baby for seven days in the ICU, under medical observation. Meanwhile, we managed to bring Praba (along with Podu) to Koraput in a bus so that she could see her child for the first time in over a week. And then the doctors told us they did not have the facilities and expertise required for a paediatric surgery.

The baby would have to be taken to yet another hospital. That one was some 700 kilometres away – the MKCG Medical College and Hospital at Berhampur (also known as Brahmapur). We once again waited for another ambulance and braced ourselves for yet another long journey.

The ambulance came from a state facility, but since the area is sensitive, we had to pay around Rs. 500 for expenses. (My friends and I took care of these costs – we spent a total of around Rs. 3,000-4,000 over those several journeys to hospitals). It took us, I recall, more than 12 hours to reach the hospital at Berhampur.

People of Tentapali returning from Chitrakonda after a two-hour water journey; this jeep then takes them a further six kilometers to their hamlet. It’s a recently shared service; in the past, they would have to walk this distance

By then, we had gone to four different hospitals by van, tractor, multiple ambulances and bus – at Chitrakonda, Malkangiri headquarters, Koraput and Berhampur – and covered nearly 1,000 kilometres.

The surgery was critical, we were informed. The baby’s lungs too were damaged and a portion had to be surgically removed. An opening was made in the stomach to enable the removal of faecal waste. A second operation would be required to create a regular opening, but that can only be done when the baby attains eight kilos of weight.

When I last checked with the family, the baby, then eight months, had not yet achieved this milestone. The second surgery is still pending.

Around a month after the baby was born despite innumerable odds, I was called for his naming ceremony. And I named him Mrutyunjay – a conqueror of death. That was on August 15, 2020, India’s Independence Day – he had been through his own midnight tryst with destiny and emerged victorious like his mother.

*****

While Praba’s ordeal was particularly difficult, in many remote Adivasi hamlets of Malkangiri district, where public health facilities and infrastructure are sparse, women are routinely at great risk in similar situations.

The Scheduled Tribes – mainly Paroja and Koya – comprise 57 per cent of the total population of Malkangiri’s 1,055 villages. And while the culture, traditions and natural resources of these communities and region are celebrated in various accounts, the healthcare needs of the people here are largely ignored. The topography – hills, forest areas and water bodies – along with the long years of conflict and the state’s neglect have meant that access to life-saving services in these villages and hamlets is minimal.

‘The menfolk hardly realize that we women too have a heart and we also feel pain. They think we are born to deliver babies’

At least 150 villages in Malkangiri district don’t have road connectivity (the total across Odisha without road links is 1,242 villages, Pratap Jena, Minister of Panchayati Raj and Drinking Water, said in the state Assembly on February 18, 2020).

Among these is Tentapali, around two kilometres from Kotaguda, which too is inaccessible by road. “Babu, our life is marooned with water all around, so who bothers whether we live or die?” says Kamala Khillo, who has lived all her 70-odd years in Tentapali. “We have spent most part of our lives seeing only this water, which adds to the miseries of women and young girls.”

To reach other villages, the people of Tentapali, Kotaguda and three other hamlets of Jodambo panchayat in the reservoir area commute by motorboat undertaking journeys that range from 90 minutes to over four hours. To get to the healthcare facilities at Chitrakonda, 40 kilometres away, the boat remains the most viable option. To reach the CHC some 100 kilometres away, people living here have to take a boat and then journey onward by bus or shared jeeps.

The motor launch service provided by the Department of Water Resources is unreliable, with the frequent and unscheduled suspension of services. And these boats generally make only one journey across and one back in a day. A privately-run powerboat service, at Rs. 20 per ticket, costs 10 times more than the state-run launch. It too stops plying by evening. So in an emergency, transportation remains a huge problem.

“Whether it’s for Aadhaar or to consult a doctor, we have to rely on these [modes of transport] and that is why many women are reluctant to visit the hospital for their deliveries,” says Kusuma Naria, a 20-year-old mother of three from Kotaguda.

Samari Khillo of Tentapali hamlet says: ‘We depend more on daima than the medical [services]. For us, they are doctor and god’

Now though, she adds, ASHA workers have been visiting these remote hamlets. But the ASHA didis here are not too experienced or well-informed, and they only visit once or twice a month to give iron pills, folic acid tablets, and dry food supplements to pregnant women. Records of children’s immunisation remain scattered and incomplete. On occasion, when a difficult childbirth is anticipated, they accompany the pregnant woman to the hospital.

In the villages here, there are no regular meetings and awareness camps, no discussions with women and adolescent girls about their health concerns. The meetings the ASHA workers are supposed to organise in school buildings also rarely happen because there is no school in Kotaguda (though there is one in Tentapali, where teachers have never turned up regularly) and the anganwadi building is incomplete.

Jamuna Khara, an ASHA worker in the area, says that because the PHC in Jodambo panchayat can only offer basic treatment for minor ailments and has no facilities for pregnant women or for complicated cases, she and other didis prefer the Chitrakonda CHC. “But it is too far and a proper journey by road is not possible. The boat is risky. The government launch does not run at all times. So for years now, we have depended on daima [traditional birth attendants, TBAs].”

Samari Khillo of Tentapali hamlet, a Paroja Adivasi, confirms this: “We depend more on daima than the medical [services]. My three children were delivered with the help of dais only – our village has three of them.”

Women from around 15 adjacent hamlets here depend on the bodhaki dokari – as the TBAs are referred to in the local Desiya language. “They are a boon for us as we can become mothers safely without visiting medical centres,” adds Samari. “For us, they are doctor and god. As women, they too understand our agony – the menfolk hardly realise that we too have a heart and we also feel pain. They think we are born to deliver babies.”

Gorama Nayak, Kamala Khillo, and Darama Pangi (l to r), all veteran daima (traditional birth attendants); people of around 15 hamlets here depend on them

The dais here also give local medicinal herbs to women who can’t conceive. If these don’t work, their husbands sometimes re-marry.

Kusuma Naria, who got married at the age of 13 and gave birth to three children by the time she was 20, told me that she did not even know about menstruation, let alone contraception. “I was a child and knew nothing,” she says. “But when it [menstruation] happened, mother asked to use cloth and then quickly got me married, saying that I had become a grown-up girl. I didn’t know anything about physical relationships either. During my first delivery, he left me all alone in the hospital, uncaring if the baby died – because she was a girl. But my girl survived.”

Kusuma’s two other kids are boys. “When I refused to have a second child after a short gap, I was beaten because everyone was hoping for a boy. Neither I nor my husband had any idea of dawai [contraceptives]. Had I known, I would not have suffered. But had I opposed, I would have been driven out of the house.”

Not far from Kusuma’s house in Kotaguda lives Praba. She said to me the other day: “I can’t believe I am alive. I don’t know how I took all that was happening then. I was in terrible pain, my brother was crying, unable to see me in such pain. Then the journey from hospital to hospital, then this baby and my not even being able to see him for some days. I don’t know how I survived it all. I pray to god no one should have such experiences. But we are all ghati [mountain] girls and life is the same for us all.”

Praba’s experience of giving birth to Mrutyunjay – and the stories of very many women in the villages here, and of how women give birth in these parts of tribal India – are quite incredible. But does anyone care about what happens in our Malkangiri?

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org