After a lifetime of illness and surgeries, including a uterus removal, Bibabai Loyare of Hadashi village in Pune district is bent and sunken. Still, she continues to do farm work and looks after a paralytic husband.

“What can I tell you? My back is broken and my rib cage is protruding,” Bibabai Loyare says. “My abdomen is sunken, my stomach and back have come together over the last 2 or 3 years. And the doctor says my bones have become hollow.”

We are sitting in a dimly lit kitchen, made from tin sheets, adjacent to her house in Hadashi village in Mulshi block. Bibabai, around 55 years old, is heating leftover rice in a pan over a mud stove. She gives me a wooden paat (low platform) to sit on and continues with her chores. When she gets up to do the dishes, I see that she is bent so completely from the waist that her chin could almost touch her knees. And when she sits with her legs drawn up, her knees touch her ears.

Osteoporosis and four surgeries in the last 25 years have left Bibabai this way. First, she went through a tubectomy procedure, then a surgery for hernia, followed by a hysterectomy, and then an operation that excised part of her intestines, abdominal fat and muscles.

“I was married at 12 or 13, just as I came of age [had her first period]. I did not conceive for the first five years,” says Bibabai, who didn’t get to go to school at all. Her husband, Mahipati Loyare – or Appa, as everybody knows him – is 20 years older than her and a retired zilla parishad school teacher, who was posted in various villages in Mulshi block of Pune district. The Loyare family cultivates rice, Bengal gram, beans and legumes on their farmland. They also have a pair of bullocks, a buffalo and a cow and her calf, and milk fetches them an additional income. Mahipati also gets a pension.

“All my children were born at home,” Bibabai continues. Her first child, a boy, was born when she was just 17. “We were on our way to my parents’ home [in a village “beyond the hill range”] in a bullock cart as there was no pucca road and no vehicles in our village at the time. My water broke, I went into labour, and soon my first child was born, right there in that bullock cart!” Bibabai recalls. She needed an episiotomy later to repair the perineal tear – she does not recall where this was done.

‘My back is broken and my rib cage is protruding. My abdomen is sunken, my stomach and back have come together…’

During her second pregnancy, Bibabai remembers that doctors at a private clinic in Kolwan, a larger village just two kilometres from Hadashi, had said that her haemoglobin was low and foetal growth was below normal. She remembers getting 12 injections from a nurse in the village, and iron tablets. After completing full term, Bibabai gave birth to a girl. “The child never cried or made a sound. Lying in her cradle, she would keep staring at the ceiling. Soon, we realised that she was not normal,” Bibabai says. The girl, Savita, is 36 years old now. She was diagnosed at the Sassoon Hospital in Pune as “mentally retarded” – or intellectually disabled. Though she seldom speaks to outsiders, Savita helps with the farm work and does most of the household chores.

Bibabai gave birth to two more children, both boys. The youngest, her fourth child, was born with a cleft lip and palate. “If I fed him milk, it would come out of his nose. The doctors [at a private clinic in Kolwan] had told us about a surgery that would have cost 20,000 rupees. But at the time, we lived in a joint family. My husband’s father and elder brother did not pay much attention [to the need for surgery], and my child died in a month,” says Bibabai, sadly.

Her elder son now works on the family farm, and the younger son, her third child, works as an elevator technician in Pune.

After the death of her fourth child, Bibabai got a tubectomy done at a private hospital in Pune, around 50 kilometres from Hadashi. She was in her late 20s by then. Her elder brother-in-law took care of the costs, and she does not recall the details. A few years after the sterilisation procedure, she developed a chronic stomach ache and a big bulge on her left side – though Bibabai says it was just ‘gas’, doctors diagnosed a hernia. It was so bad that it was pressing on the uterus. The hernia was operated upon at a private hospital in Pune. Her nephew handled the expenses; she does not know how much it cost.

Bibabai resumed strenuous farm labour soon after a hysterectomy, with no belt to support her abdominal muscles

Then, in her late 30s, Bibabai started getting dangerously heavy periods. “The bleeding was so profuse that while working on the farm, blood clots would fall on the ground. I would simply cover them with soil,” she recalls. After enduring this for two whole years, Bibabai saw a private doctor yet again at a clinic in Kolwan. He told her that her uterus was damaged (‘pishvi naasliye’) and would have to be removed urgently.

So, when she was around 40, Bibabai had a hysterectomy, a surgery to remove the womb, at a well-known private hospital in Pune. She spent a week in the general ward. “The doctors had prescribed a belt [to support the abdominal muscles] after the surgery, but my family never got one,” Bibabai says; perhaps they didn’t realise the importance of the belt. She didn’t get enough rest either, and resumed work on the farm soon after.

Though advised not to undertake any strenuous activities for 1 to 6 six months after this surgery, women in the agricultural sector “do not have the luxury to take rest for such a long period” and usually return to work soon after, notes a paper on hysterectomy among premenopausal rural women, by Nilangi Sardeshpande, published in the International Research Journal of Social Sciences in April 2015.

Much later, one of Bibabai’s sons got her two belts. But she cannot use them now. “You see, I do not have any lower abdomen left, and the belt does not fit,” she says. Around two years after the hysterectomy, Bibabai (she does not recall details such as dates and years) had yet another surgery, at another private hospital in Pune. “This time,” she says, “the intestines were [partially] removed too.” Pulling down the knot in her nine-yard saree, she shows me her almost concave abdomen. No flesh, no muscles. Just some wrinkled skin.

Bibabai is hazy about the details of this abdominal surgery, or exactly what occasioned it. But Sardeshpande’s paper points out that post-operative injuries to the bladder, bowels and ureters are a frequent complication of hysterectomy. Almost half of the 44 premenopausal women interviewed in rural areas of Pune and Satara districts, who had bene through a hysterectomy, reported immediate post-operative difficulties in urinating and severe pain in the abdomen. And many said they faced long-term health problems after the surgery, and got no relief from the abdominal pain they had been suffering before the surgery.

Despite her health problems, Bibabai Loyare works hard at home (left) and on the farm, with her intellactually disabled daughter Savita’s (right) help

In addition to all this, Bibabai has developed severe osteoporosis over the last 2 to 3 years. Osteoporosis is a frequent fallout of hormonal imbalances following hysterectomy and early menopause. The osteoporosis has made it impossible for Bibabai to straighten her back now, even while sleeping. Her problem has been diagnosed as ‘osteoporotic compression fractures with severe kyphosis’, and she is under treatment at a private hospital in Chikhali in the industrial township of Pimpri-Chinchwad, around 45 kilometres away.

She hands me a plastic bag containing her reports. A life full of pain and illness, and her file contains just three sheets, one X-ray report, and a few receipts from chemists. She then carefully opens a plastic box and shows me a strip of capsules that relieve her pain and discomfort. These are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that she takes when she has to do any strenuous work such as cleaning a sack full of broken rice.

“The arduous physical labour and the daily drudgery in these hilly terrains, coupled with malnutrition, have disastrous effects on women’s health,” says Dr. Vaidehi Nagarkar who has been practising medicine in Paud village, around 15 kilometres from Hadashi, for the last 28 years. “At our hospital, I see some progress in the number of women seeking healthcare for reproductive illnesses, but chronic ailments such as iron deficiency anaemia, arthritis and osteoporosis still remain untreated.”

“And bone health, which is crucial for efficiency in farm work, is a completely neglected health concern, especially in ageing populations,” adds her husband Dr. Sachin Nagarkar.

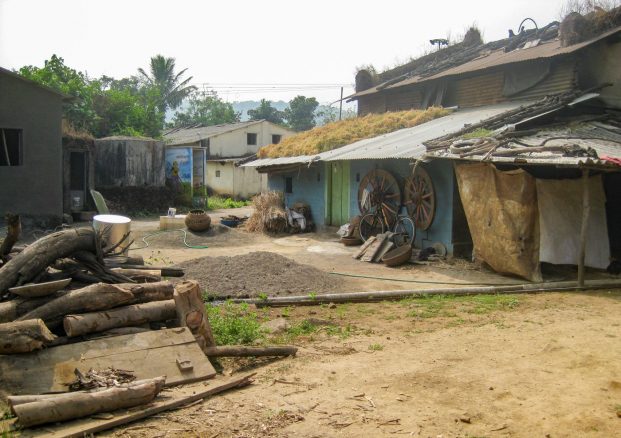

The rural hospital in Paud village is 15 kilometres from Hadashi, where public health infrastructure is scarce

Bibabai knows why she has suffered so much: “In those days [20 years ago], the entire day, from morning to night, we were out working. It was hard labour. Seven to eight rounds of dumping cow dung on our fields high up on a hill [roughly three kilometres from her home], fetching water from the well or wood for fuel…”

Even now, Bibabai helps on the farmland that her eldest son and daughter-in-law cultivate. “A farmer’s family never really rests, you know,” she says. “And for the woman, it does not matter if she is pregnant or sick.”

There is scarcely any public health infrastructure in Hadashi, a village with a population of 936. The nearest health sub-centre is in Kolwan, and the nearest primary health centre is in Kule village, 14 kilometres away. Bibabai’s long decades of seeking healthcare from private practitioners and private hospitals were perhaps partly due to this – though the decisions of which doctors and hospitals to visit were at all times made by the men in her joint family.

Unlike many people in rural Maharashtra, Bibabai has always had little faith in bhagats (traditional healers) or devrushis (faith healers), and visited a faith healer only once in her village. “He made me sit in a big round plate and poured water over my head as if I was a child. I simply hated it. That was the only time,” she recalls. Her faith in modern medicine is an exception, and may have something to do with her husband’s education and occupation as a school teacher.

By now it is time for Appa’s medicine, and he calls out to Bibabai. Around 16 years ago, two years before he was due to retire, Appa, now 74, had a paralytic stroke that left him almost bedridden. He cannot speak, eat or move much on his own. Sometimes he drags himself from his bed to the door. On my first visit to their home, he got annoyed because Bibabai got talking to me and delayed giving him his medicine.

Bibabai feeds him four times a day, and gives him his medicines and salt water to treat his sodium deficiency. She has been doing this for 16 years, on time and with love, regardless of her own health problems. She struggles stoically to do as much of the farm and household work as she can. Even after decades of work and pain and ill-health, as she says, a woman in a farmer’s household can never rest.

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org