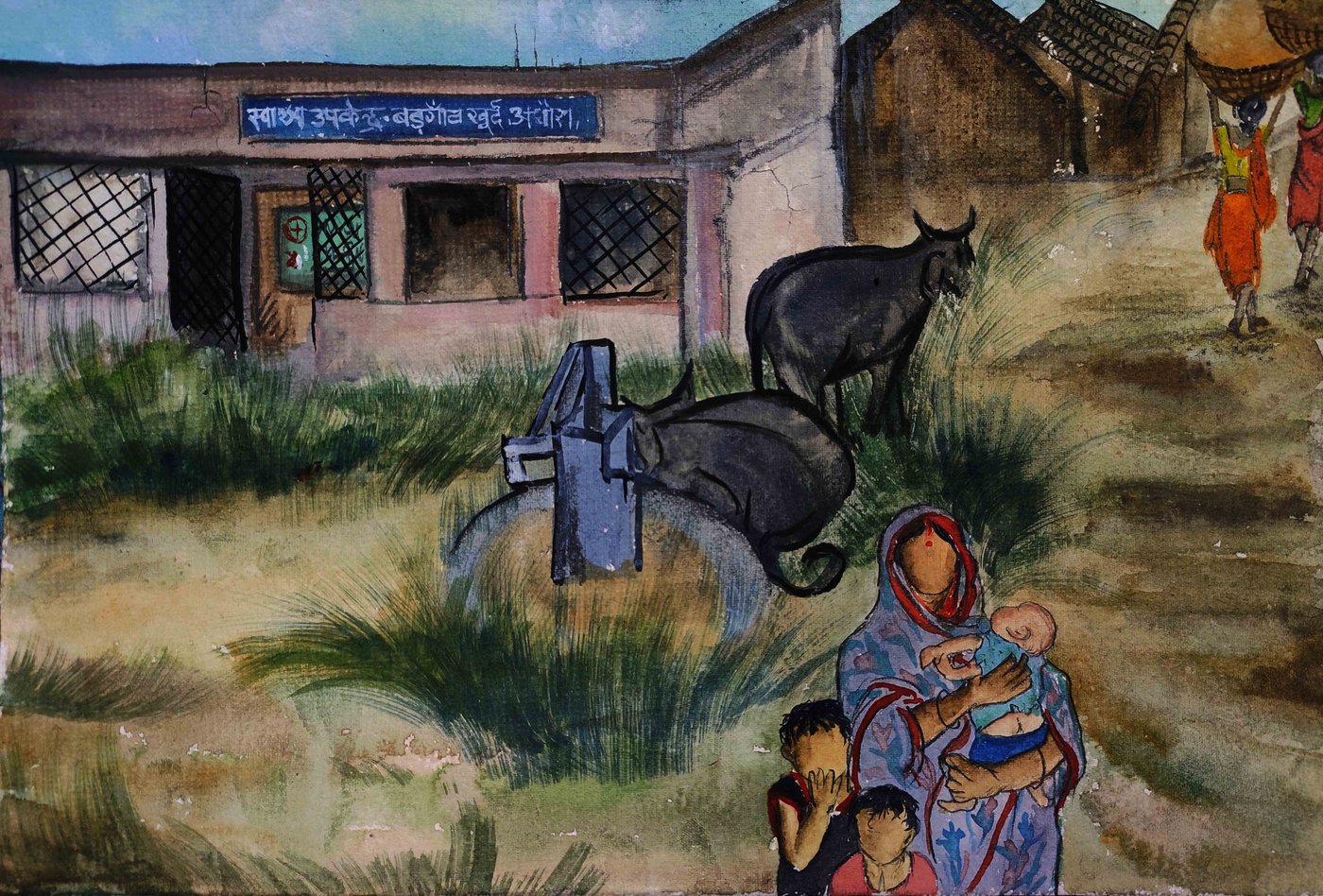

An understaffed PHC where wild animals wander in, fears about hospitals, poor phone connectivity – all ensure that pregnant women in Bihar’s Baragaon Khurd village invariably deliver at home

The monsoon had subsided. The women of Baragaon Khurd village in Bihar were fetching mud from the fields to layer the outer walls of their kutcha houses, a strengthening and beautifying task they do every now and then, especially before festivals.

Leelavati Devi, 22, wanted to step out to collect mud with the other women. But her baby boy, three months old, was wailing and refusing to fall asleep. Her husband, 24-year-old Ajay Oraon, was away at the grocery shop he runs in the vicinity. The baby lay nestled in her arms and every few minutes, Leelavati placed her palm on his forehead as if to check for a fever. “He is fine, at least I think so,” she said.

In 2018, Leelavati’s daughter, 14 months old, had developed a fever and passed away. “It was just two days of fever, not high,” Leelavati said. Beyond that, the parents are unaware what caused the death. There are no hospital records, no prescriptions, no medicines. The couple had planned to take her to the primary health centre (PHC), nine kilometres from their village in Adhaura block of Kaimur district, if the fever did not subside for another few days. But they didn’t end up doing so.

The PHC, located close to the forested area of the Kaimur Wildlife Sanctuary, does not have a boundary wall. The residents of Baragaon Khurd village and the adjoining Bargaon Kalan recount stories of wild animals – sloth bears, leopards and a nilgai – wandering into the building (the two village have a common PHC), scaring patients and relatives, as well as healthcare workers who are not keen to serve here.

“There is a sub-centre too [in Baragaon Khurd], but the building is abandoned. It has become a resting shed for goats and other animals,” says Phulwasi Devi, an accredited social health activist (ASHA) who has persisted on the job since 2014 – with limited success, by her own standards.

In 2018, Leelavati Devi and Ajay Oraon’s (top row) baby girl developed a fever and passed away before they could take her to the PHC located close to the Kaimur Wildlife Sanctuary. But even this centre is decrepit and its broken-down ambulance has not been used for years (bottom row)

“The doctors live in Adhaura [town, around 15 kilometres away]. There is no mobile connection, so I cannot contact anyone in an emergency,” says Phulwasi. Despite this, over the years, she estimates she has brought at least 50 women to the PHC or the referral unit of the Mother and Child Hospital (located next to the PHC), another decrepit building that has no female doctors. All responsibilities here are handled by the auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) and a male doctor, both of whom don’t live in the village and are difficult to contact in emergencies if there is no telecom signal.

But Phulwasi soldiers on, taking care of the 85 families (population 522) in Baragaon Khurd. The majority, including Phulwasi, are from the Oraon community, a Scheduled Tribe, their lives and livelihoods centred around agriculture and forests. Some of them own patches of land on which they cultivate mainly paddy, some go to Adhaura and other towns looking for daily wage labour.

“You are thinking it’s a small number, but the government’s free ambulance service doesn’t run here,” Phulwasi says, pointing to an old and broken-down vehicle that has been standing outside the PHC for years. “And people have misconceptions about hospitals, the copper-T and contraceptive pills [about how the copper-T is inserted, or that the pills cause weakness and dizziness]. Most of all, who has time here after all the household work for ‘awareness’ campaigns – about mother-and-child, polio and so on’?”

These healthcare hurdles were reflected in our conversations with the pregnant women and new mothers in Baragaon Khurd. All the women we spoke to had delivered their children at home – even though National Family Health Survey ( NFHS-4 , 2015-16) data for Kaimur district says that 80 per cent of deliveries in the preceding five years were institutional childbirths. NFHS-4 also notes that no child born at home was taken to a health facility for check-up within 24 hours of birth.

At another home in Baragaon Khurd, 21-year-old Kajal Devi has returned to her in-laws’ house with her four-month-old baby boy after the childbirth at her parents’ place. There was no consultation or check-up with a doctor during the entire pregnancy. The child has not been vaccinated so far. “I was at my mother’s house so I thought I’ll get him vaccinated once I return home,” Kajal says, unaware that she could have got her child vaccinated even at her parents’ house in the neighbouring Bargaon Kalan, a slightly bigger village with 108 households and a population of 619, which has its own ASHA worker.

The hesitation to consult a doctor stems from fears and, in many instances, the preference for a male child. “I have heard that children get exchanged in hospitals, especially if it’s a boy, so it’s better to deliver at home,” Kajal replies, when asked why she chose to deliver her baby at home with the help of elderly women from the village.

Another resident of Baragaon Khurd, 28-eight-year-old Sunita Devi, says she too delivered at home without the assistance of a trained nurse or doctor. Her fourth child, also a girl, is fast asleep in her lap. Through all her pregnancies, Sunita never went to the hospital for a check-up or a delivery.

“There are many people at the hospital. I can’t give birth in front of people. I feel shy, and if it’s a girl, it’s worse,” Sunita says, unwilling to believe Phulwasi when she says hospitals can take care of privacy.

“Delivering at home is best – get the help of an old woman. After four children, you don’t need too much assistance anyway,” Sunita laughs it off. “And then this person comes to give an injection and you feel better.”

The person coming to give the injection is a “ bina -degree doctor” (a doctor without a degree) as some in the village call him, from the Tala market seven kilometres away. No one is entirely certain what his qualifications are or what the injection he administers contains.

Sunita looks at the baby sleeping in her lap and, in the course of our conversation, vacillates between guilt at having given birth to another girl, worry about how she will get all her daughters married, and concern for her husband, who has no male family member to help him in the field.

Top left: ‘After four children, you don’t need much assistance’, says Sunita Devi. Top right: Seven months pregnant Kiran Devi has not visited the hospital, daunted by the distance and expenses. Bottom row: The village’s abandoned sub-centre has become a resting shed for animals

Except for 3-4 weeks preceding her deliveries and after, Sunita goes to the field every afternoon after finishing the household work. “It’s just a little work – sowing and all, not much,” she murmurs.

A few houses away from Sunita’s lives Kiran Devi, 22, seven months pregnant with her first baby. She hasn’t been to the hospital even once, daunted by the distance she will have to walk to reach there and the expense of hiring a vehicle. Kiran’s mother-in-law passed away a few months ago (in 2020). “Shivering, she died here itself. How will we go to the hospital anyway?” Kiran asks.

If someone suddenly becomes ill in either of these villages, Baragaon Khurd or Bargaon Kalan, the choice is limited: the common PHC, unsafe without a boundary wall; the referral unit of the Mother and Child Hospital (the actual hospital is part of the Kaimur district hospital) where the sole doctor may not be available; or the hospital at the Kaimur district headquarters in Bhabua, around 45 kilometres away.

Often, people from Kiran’s village cover this distance on foot. A few buses with no fixed timetable and private pick-up vehicles ply in the name of connectivity. And the struggle to find a spot of network on mobile phones remains acute. Villagers here can spend weeks without being connected to anyone.

Phulwasi brings out her husband’s phone, “a well-kept useless toy,” she says, when asked what would help her do her job just a little better.

Not a doctor or nurse – but better connectivity and communication – she says: “One bar on this would change many things.”

Cover illustration: Labani Jangi, originally from a small town of West Bengal’s Nadia district, is working towards a PhD degree on Bengali labour migration at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata. She is a self-taught painter and loves to travel.

PARI and CounterMedia Trust’s nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org